Discover Dragon Gate: The Entrance to Chinatown

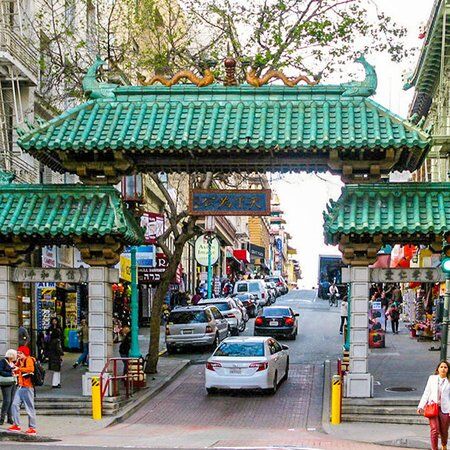

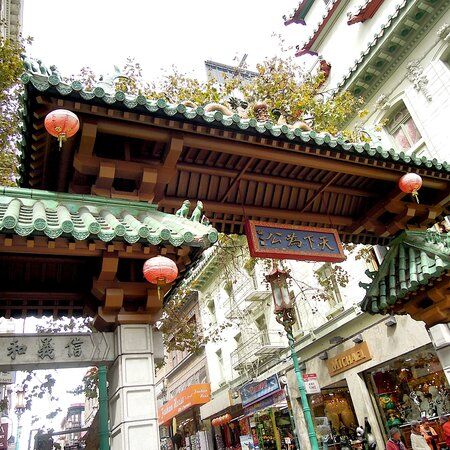

For many, the sight of pagoda roofs and dragon gates is synonymous with Chinatown. However, for Chinese tourists, or visitors with Chinese descent, the aesthetic is far from traditional, since it is actually a blend of Chinese details and American influences. The Dragon Gate though, with its stone pillars, green-tiled pagodas, and dragon sculptures, is the only authentic Chinatown gate in the United States, making it a significant cultural landmark.

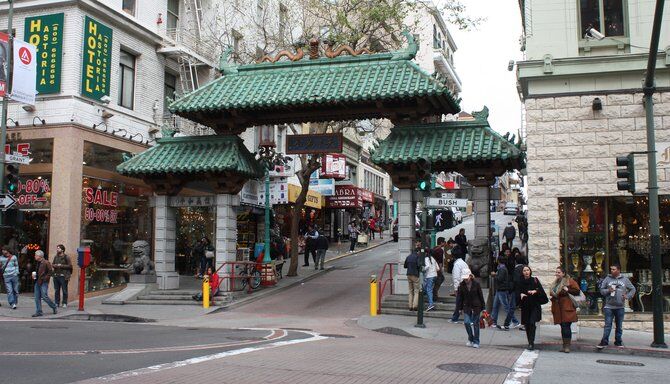

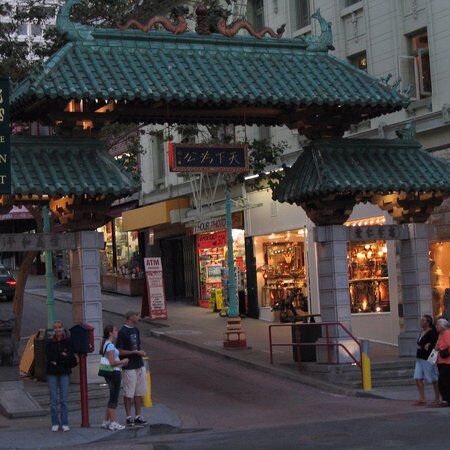

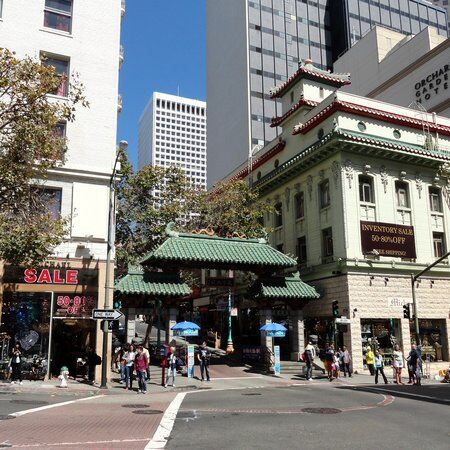

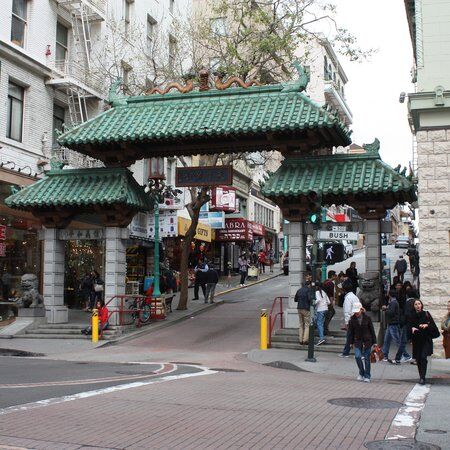

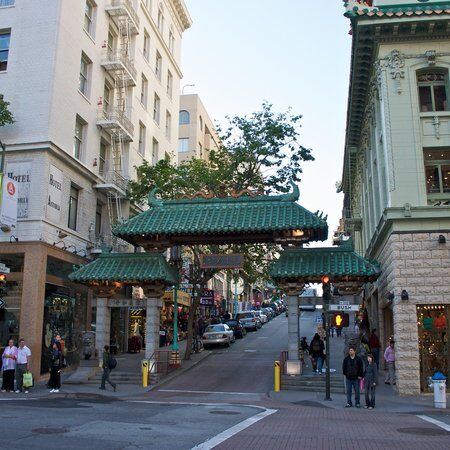

Proudly marking the southern entrance to San Francisco's Chinatown, the Dragon Gate stands at the intersection of Grant Avenue and Bush Street. The jade green roofed portal, designed in the traditional Chinese pailou style, was gifted by Taiwan and opened in 1970. Today, it allows cars and pedestrians to pass into one of the most vibrant neighbourhoods in the city.

The History of San Francisco's Chinatown

Early Challenges in Chinatown

Established in the 1850s during the Gold Rush, Chinatown in San Francisco was a haven for Chinese immigrants seeking fortune and new beginnings in America. For nearly two centuries it has been the centre of Chinese culture in the city. But it has had to endure many challenges along the way, such as discriminatory laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This Act significantly impacted the Chinese community—keeping men and their families separated—creating a bachelor society for many decades.

The neighbourhood faced further hardship during the 1906 earthquake. The earthquake damaged neighbourhoods throughout San Francisco, but in Chinatown residents' homes and businesses were dynamited by the fire department in an attempt to control the spreading fires.

To learn more about the triumphs and hardships of this community visit the Chinese Historical Society of America Museum once you have passed through the Dragon Gate!

Overcoming Challenges in Chinatown

Despite these challenges, Chinatown was resilient. After the earthquake, there were plans to replace Chinatown with white-owned businesses and relocate the Chinese community to Hunter’s Point. However, the city recognised the importance of Chinese business leaders and agreed to let Chinatown rebuild.

Local businessman Look Tin Eli spearheaded this effort in the 1920s, hiring architect T. Paterson Ross and engineer A.W. Burgren to reconstruct the area. Though neither had visited China, they drew inspiration from centuries-old images. The result was a hybrid design; American interpretation of Chinese traditional architecture.

The New Chinatown

The new Chinatown, with its pagoda-topped structures, was designed to appeal to Western tourists. And the plan worked; Chinatown became a busy tourist destination in the city. Tourists were enchanted by this version of China, which felt exotic yet safe. This influx of visitors brought much-needed capital to the neighbourhood.

The success of the new Westernised Chinese neighbourhood led other Chinatowns across the country and around the world to copy San Francisco's design. While this helped improve the public image of Chinese immigrants, it also created stereotypes and fallacies about Chinese culture.

San Francisco’s Chinatown Today

Today, San Francisco's Chinatown is one of the oldest and most famous in the United States. It spans 24 city blocks, is one of the most visited neighbourhoods in the city—attracting more tourists than the Golden Gate Bridge—and remains a key part of Chinese American history.

The annual Chinese New Year celebration, complete with a dragon parade over 200 feet long, is a highlight, drawing crowds from all over. People also come for cultural sites like the Tin How Temple, and unique experiences like creating your own fortune cookie at the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory. Or to sample delicious morsels from Good Mong Kok Bakery.

Creating the Dragon Gates in Chinatown

During the efforts to revitalise Chinatown, in 1953, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce sponsored an essay contest to generate ideas for improvement. Charles L. Leong, the winner, suggested erecting an authentic archway at Bush and Grant. This idea was well-received and by 1956, the Chinatown Improvement Committee made it a top priority, initially proposing two gates: one for Chinatown and another for the Barbary Coast red-light district.

Construction of the gates began in 1958 but was halted in 1961 and then abandoned in 1962, due to financial and material shortages. It wasn’t until 1967 that Mayor John F. Shelley tried to revitalise the project by sponsoring a design competition, with a $70,000 budget, open to architects of Chinese descent.

The winning design by Clayton Lee, Melvin H. Lee, and Joseph Yee drew inspiration from traditional Chinese village architecture. More than twenty entries were judged by a panel of architects, with the winning design praised for its openness and integration of pedestrian flow with the shops beyond.

After winning the competition, construction began in August 1968. Materials, including 120 artisanal ochre tiles, roofing, and guardian lions, were donated by the Republic of China (Taiwan) in 1969. Despite running over budget, the gate was completed in April at a cost exceeding $75,000 and inaugurated on October 18, 1970.

During the opening ceremony a half-mile-long parade was attended by 3,000 people, including Mayor Joseph Alioto and Vice-President Yen Chia-kan of Taiwan. After its creation, the Dragon Gate quickly became one of the most photographed locations in Chinatown, alongside the historic Sing Fat and Sing Chong buildings.

Repairs to the Chinatown Dragon Gate

The Dragon Gate underwent restoration in 1995, which involved replacing roof tiles, upgrading lighting, repairing steps, installing handrails, and cleaning and painting. In 2005, there was a proposal to construct a second gate at the northern entrance to Chinatown, inspired by temporary gateways used for the annual Mid-Autumn Festival. This effort, led by Wilma Pang, reflects the continuing importance of ceremonial gates in symbolising and celebrating Chinatown's cultural heritage. The Dragon Gate that exists today was actually the first ceremonial gate unveiled in the United States.

Design of the Dragon Gate in San Francisco's Chinatown

Like most traditional Chinese ceremonial gates, the Dragon Gate has three south-facing portals. The large central portal is built over the street to allow vehicles to pass and two smaller pedestrian portals at each side, go over the pavements for pedestrians. The structure is supported by stone columns, distinguishing it from many other wooden supported Chinese gateways in America. Each pedestrian portal is accessed by three small steps.

Symbolism of the Dragon Gate

Facing south in accordance with Feng Shui principles, the Dragon Gate is a dramatic entry to San Francisco's Chinatown. Inspired by ceremonial entrances to traditional Chinese villages, the jade green roof is topped with fish and dragon motifs, symbolising prosperity, fertility, and power. Stone lions guard either side of the archway. The male lion on the west holds a pearl, signifying the protection of the gate, while the female lion on the east cradles a baby lion, representing the safeguarding of the people within Chinatown.

On the centre of the gate is a four-character inscription: "天下为公," which translates to "All under heaven is for the people,” a motto attributed to Dr. Sun Yat-sen. The inscriptions above the side passages convey messages of "respect; love" on the east and "integrity; peace," on the west, core values of the Chinese community.

Beyond the Dragon Gate: Exploring Chinatown with CityDays

After passing through the Dragon Gate, there are many things to do in San Francisco’s bustling Chinatown. Visitors can wander down the main street, Grant Avenue, which is lined with shops selling everything from traditional Chinese medicines, to souvenirs and artwork.

The "Heart of Chinatown," Portsmouth Square, is a lively gathering place where locals play games of chess and practice tai chi. The square has several monuments and plaques commemorating significant events and figures in Chinese-American history. And of course, no visit to Chinatown is complete without trying some traditional cuisine—try the dim sum, steamed buns, kung pao chicken, and other delicacies.

If you want to discover the scars left behind by the earthquake that rattled through Chinatown in 1906, why not embark on a CityDays Scavenger Hunt? Scavenger Hunt tours are a great way to bring family and friends—or even dates—together for an afternoon of great fun and adventure, solving clues and snapping photos. Clues will lead you to the big sights and those that you'd walk straight past.

Our Shattered Earth Hunt is the perfect way to experience the Dragon Gate and beyond, incorporating some of the best sculptures, historic architecture and bars and cafes San Francisco has to offer. As is so relevant when experiencing Chinese culture, our hunts will fully immerse you in the character, sounds, sights and smells of one of the largest Chinese communities outside Asia.

For more information about our San Francisco Scavenger Hunts then click here: Top 6 Immersive San Francisco Scavenger Hunts & Treasure Hunts | CityDays