History of State Library Victoria

State Library Victoria proudly opened its doors on 11 February 1856, welcoming a new era of social progression in what was becoming the most rapidly growing colony in Australia.

At just over twenty years old, Melbourne was experiencing huge changes: the Gold Rush, increasing population and wealth, and hopeful signs of changing social attitudes.

Read on to find out how State Library Victoria made its mark on the history of Melbourne and Victoria…

1850s Melbourne: Expansion, Literacy & Social Change

1851 would go down in history as the year that changed everything: Victoria was declared a separate colony to that of New South Wales and Charles La Trobe was appointed as the state’s first Lieutenant Governor. Later that same year, two men struck gold in the Victorian town of Ballarat.

Thanks to the Victorian Gold Rush of 1851, Melbourne’s days of tents and timber-framed buildings were over. Plans were drawn up to erect new, grandiose stone buildings and a concentrated effort was made to put a portion of the wealth generated by gold back into Australia’s colonies - and one of the first projects on the list was State Library Victoria.

Until the Gold Rush, most immigrants from Europe to Australia fell into one of two categories: convicts or free settlers. The vast majority of them had experienced little or no schooling. Immigrants from the United Kingdom, for example, were considered literate if they could sign their name on a marriage certificate - which, despite being a very low bar, far from everyone could achieve. The same was still true for many of the thousands of miners arriving in the colony.

But times were changing. The Victorian Government recognised that as well as the much-needed labour force, the newly-founded colony would prosper better if its population had “desirable” traits such as literacy.

In 1850, the European population of Victoria was 69,739 and an estimated 6807 children attended either a church, public or private school. By 1860, those numbers had more than doubled. The population of the state had risen to 548,412, and the number of children enrolled in school had risen to 51,668.

But it wasn’t just children that needed educating. In 1850, the UK Parliament passed The Library Act, giving local councils in England the authority to establish free public libraries. Few reacted immediately, but in Victoria, the idea was embraced with open arms.

1853-1856: State Library Victoria is Born

In January 1853, the newly-formed Legislative Council of Victoria voted in favour of spending £3000 on books and £10,000 for building Australia’s first public library - what we now call State Library Victoria.

The plan was widely approved of by the public; free access to literature, newspapers and study materials was an unprecedented step forwards for working class people and signalled a step in the right direction. Spearheading the operation were a group of trustees who were appointed on 20th July - one of whom was Redmond Barry, the Solicitor-General of Victoria, best known for sentencing Ned Kelly to death.

A competition was released the same year to allow architects to submit their proposals for what Melbourne Public Library (the original name of State Library Victoria) should look like. The winner would receive £150 for his efforts and the runner-up £75. As it happened, first prize went to Joseph Reed, a Cornishman who had emigrated to Melbourne just one year earlier, while second prize went to a Mr. Burgoyne.

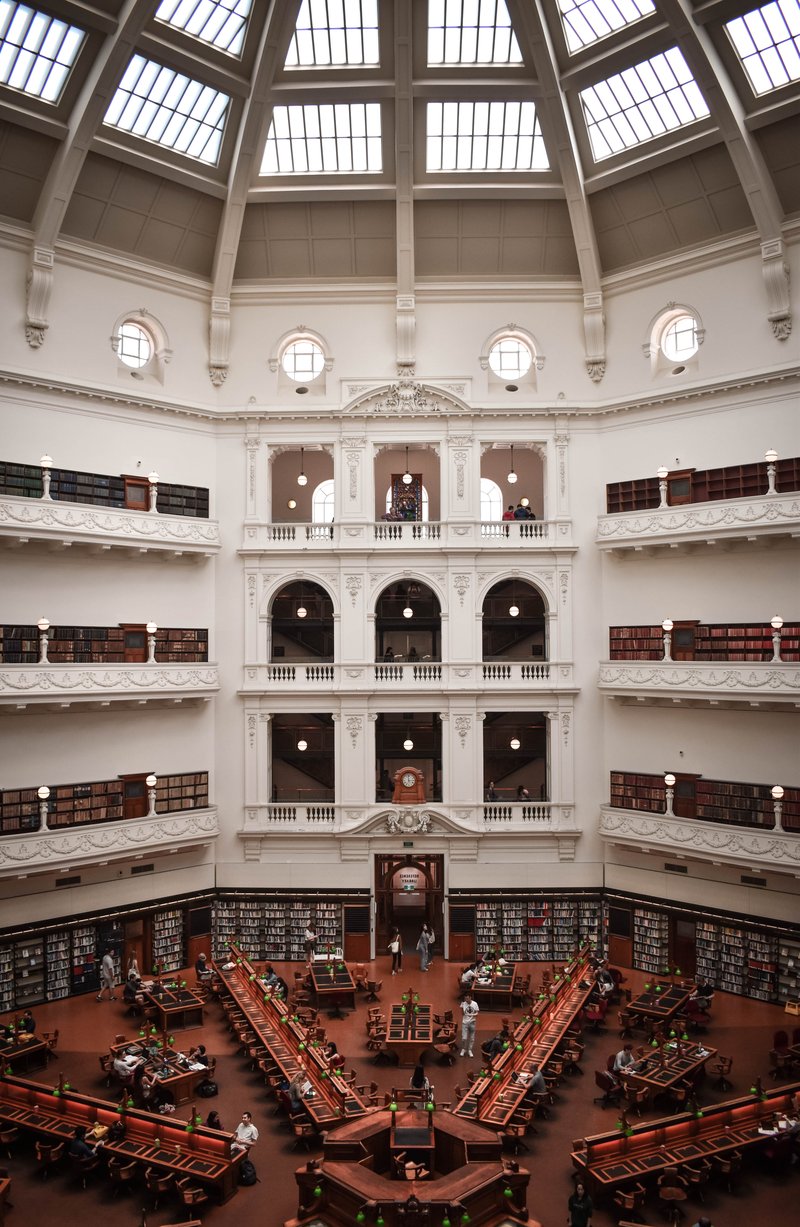

Reed’s plan for Melbourne Public Library was to evoke grandeur and a sense of Neoclassical Italy. His design for the library showed a stunning example of Classical Revival architecture, complete with ornate designs and high-domed ceilings.

State Library Victoria was designed to serve as a multi-use space, combining a library, museum and gallery. The centre of the building was built first, which consisted of two stories: the ground floor serving as an entrance and the second floor for housing books. The other wings, floors and front of the building were added later, along with the museum, a meeting and librarian’s room, offices and even rooms for unpacking and repairing books.

State Library Victoria An Ongoing Project

Over its long life, State Library Victoria has been a continuous work in progress. When it opened in 1856, only the centre portion of the library was available to the public. Just a few months after opening, gas was installed in the library, enabling readers to continue browsing books after daylight hours.

In the years that followed, new reading rooms, wings and aesthetic changes to the outside of State Library Victoria. By 1859, the Queen’s Reading Room had been added, and five years later in 1864, Palmer Hall was opened to the public.

As recently as 2018, State Library Victoria opened new entrances to the building, making the library accessible from Russell and La Trobe street. In 2019, the Victoria Gallery (previously the La Trobe Gallery staff space) was opened.

In 2015, plans for a five-year redevelopment plan named Vision 2020 for State Library Victoria was initiated. This included a $55.4 million budget provided by the Victorian Government and a further $28 million from philanthropic organisations.

A significant contribution was made by John and Pauline Gandel, from Gandel Philanthropy, who donated $2 million to create the Children’s Quarter and provide free literacy programs made by children, for other children. The Children’s Quarter was renamed the Pauline Gandel Children’s Quarter in their honour.

State Library Victoria: Education and Equality

In some respects, the opening of Melbourne Public Library was an experiment. Until then, social segregation had been a natural part of Western society. Men and women had designated spaces for socialising, a rigid class system upheld by wealth, status and background ensured people from opposite ends of society didn’t rub shoulders unless necessary, and a person’s race and ethnicity also determined who they socialised with and how they would be perceived.

When the library opened, it endeavoured to create a neutral and ‘classless’ public space where ‘anyone’ could use the building and use it for its purpose, rather than according to their status. As well-intentioned as this change was, it would not occur overnight.

Rules were implemented to the library that users had to abide by in order to use the space. Many of them were obvious, such as adhering to opening hours, not removing books from the library (initially there were no duplicates, so if a book was taken out then it would be unavailable to all), replacing books where you found them and not defacing public property.

Other rules, with today’s mindset, come across as prejudiced and snobbish. One such rule ‘advised’ patrons of the library’ to dress ‘decently’. In 1856, a man was turned away from the library after his hands were shown to be dirty, and since the building had no lavatory, he couldn’t wash them onsite.

However, by and large, Melbourne Public Library successfully helped to close the gap between rich and poor European Australians. Just two years after opening, the Perth Inquirer and Commercial News reported:

“The library is by no means exclusively frequented by the richer classes, for working men may be observed there nearly at all times…Nor is it confined to the one sex. Ladies are frequent visitors, though by no means in such numbers as might be expected or desired.” – The Inquirer and Commercial News, 18 August 1858

On the other hand, a few groups are noticeably absent from the reports of the library’s early successes: namely, people of non-white origin such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Asian and other minority groups.

Today, things are thankfully very different. State Library Victoria prides itself on prioritising Inclusion, Diversity and Access for all, with schemes in place to help disadvantaged groups who face physical, geographic, economic or social barriers. Read more here.

State Library Victoria: See and Do

Visiting State Library Victoria should be at the top of any visitor to Melbourne’s list. This rich, historic building is a treasure trove of information, and regularly features as one of the city’s most instagrammable buildings.

Whether you’re a bibliophile, lover of architecture or you just want to explore fascinating collections, State Library Victoria is absolutely the place to do it. Here are a few key things to keep an eye out for:

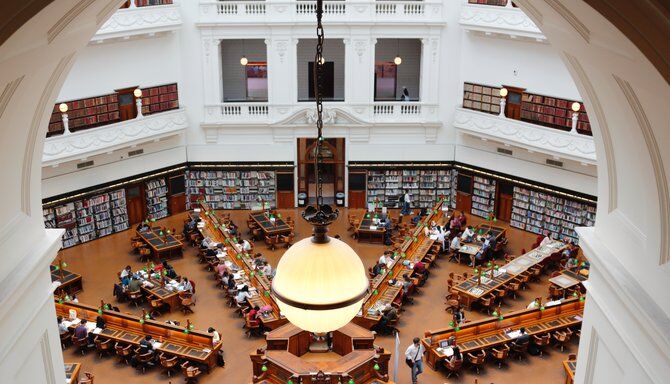

Visit La Trobe Reading Room

Probably the most famous room in State Library Victoria, the La Trobe Reading Room with its large dome ceiling and grand, visually stunning space is the ideal place to get some peace and quiet and absorb Melbourne’s bountiful sunlight.

Check Out Sculptures

State Library Victoria has numerous sculptures, busts and statues dotted inside and outside the building, each with its own history and interest. A few to look out for are the statues of Sir Redmond Barry and Joan of Arc, the busts of Stawell and Higinbotham, the bronze sculpture entitled Father and Son, and the statue of St George and The Dragon statue located in The Reserve.

Browse the Collection

With over 2 million books, along with hundreds of thousands of photographs, maps, manuscripts and works of art, you are bound to find something of interest. State Library Victoria also contains numerous rare and historic items, including the first novel printed and published in mainland Australia: The Guardian: A Tale by Anna Maria Bunn.

Services, Events and Facilities

As well as being an interesting place to visit, State Library Victoria is also incredibly useful for visitors and residents alike. Make the most of free internet access, study spaces, and cultural events that occur throughout the year - ideal for those travelling on a budget or looking for cheap things to do in Melbourne!

Discover More about Melbourne with CityDays

Ready to discover more of what Melbourne has to offer?

CityDays have FOUR treasure and scavenger hunts in Melbourne to choose from, all of which combine the fun of an escape room with the historic facts and whimsical trivia of a walking tour!

For those interested in exploring Melbourne’s Gold Rush history, check out our Frozen Idols, Shifting Walls route.

Take the stress out of planning your visit to Melbourne and book your adventure today!

Not visiting Melbourne this time? Don’t worry, you’ll find us all over the world.