A Brief History of Chinatown Melbourne

As the oldest continuous Chinatown in the Southern Hemisphere (and one of the oldest outside of Asia) Melbourne Chinatown is an urban tapestry of culture, history and hidden secrets.

Below you’ll find the history of Chinatown Melbourne, and how Victoria’s capital came to be home to this fascinating quarter.

Chinese Immigration to Victoria: Why Melbourne Has a Chinatown

Twenty or so years after modern Melbourne’s foundation in 1834, a discovery was made that would alter thousands of people’s destinies forever: miners struck gold.

Accordingly, the year 1851 saw a colossal boom in immigration to Victoria. What was to become known as The Gold Rush had begun - but it took a few years before the news reached China.

Rumours of hidden mineral treasure in Australia reached China in 1853, two years after gold had been discovered in Victoria. Accordingly, many left their families and livelihoods behind and headed for Melbourne in search of gold and better prospects.

Most of the initial Chinese immigrants to Australia were men who had their voyage sponsored by agents - something they would have to pay back through hard labour in Victoria’s gold mines.

The 1850s: How Celestial Alley Became Chinatown Melbourne

Many Chinese immigrants to Victoria arrived on ships docked on the Yarra River in Melbourne. From there, they had to make their own way to newly established gold mine towns such as Ballarat and Bendigo. But after a three month voyage, the average time it took from Hong Kong to Melbourne, even the most eager of workers needed somewhere to stay.

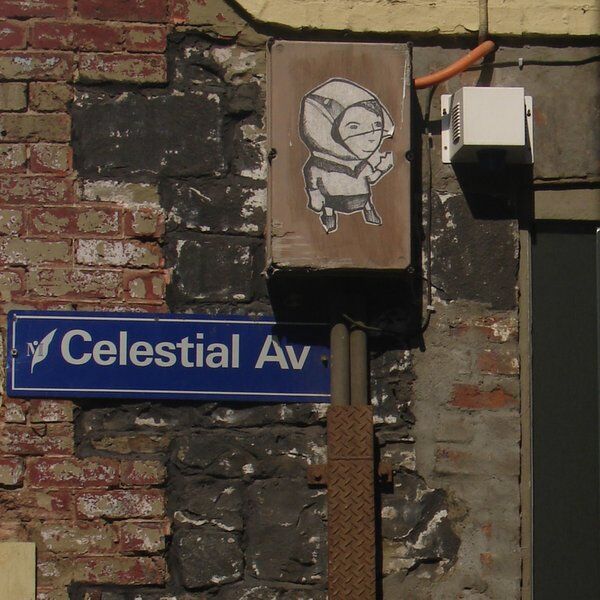

The solution was to occupy rooms in an alleyway not far from the dock. Initially, the alley was unnamed, but later became known as Celestial Alley (now Celestial Avenue). The name can be traced back to a Chinese name for China “Tianchao” meaning “heavenly dynasty”. However, ‘Celestial’ later became a byword in the United States, Canada and Australia to mean ‘Chinese’, often used in a derogatory sense.

Thus, Celestial Alley near Swanston Street was born. As more and more Chinese immigrants arrived, the small community grew and flourished. It was here that many newly-arrived Chinese men got directions for where to find the gold mines, bought and traded necessary tools and met new friends.

While many were just temporary visitors to Celestial Alley, others stayed put and still more others came back after their stint in the mines. In 1855, 19,000 Chinese people landed in Victoria. Just two years later, the Chinese population in the state had exceeded 26,000.

Psst: Did you know that Australia’s largest Chinatown is in Sydney, New South Wales? Read more here!

‘Marvellous Melbourne’: Chinatown Melbourne Grows Despite Challenges

From the mid 1850s until Federation in 1901, immigration from China to Victoria continued to grow despite increasing resistance from the Victorian Government.

Whether living on the mines or in Melbourne, Chinese immigrants were considered unwelcome competition or treated with disdain by many Europeans. Frequent conflicts arose between the two, and the Victorian Government implemented strategies to minimise Chinese immigration to the colony.

The most violent conflict between Chinese and European miners occurred on 4 July 1857, when 100 European men attacked 1000 Chinese miners and their camp. The attack resulted in the deaths of 3 Chinese miners, and countless more were severely hurt, robbed, and their temporary homes and temple destroyed. This later became known as the Buckland Riot.

In Melbourne’s Chinatown, Celestial Alley had also grown, despite the Victorian Government’s short-lived initiative to economically drive Chinese immigrants out of town. In November 1857, just a few months after The Buckland Riot, Chinese immigrants, unlike European immigrants, were forced to pay a £1 licence to remain in Victoria, which had to be renewed every two months. This policy ended in 1862 after protests and a downturn in Chinese mining immigrants.

By 1861, an estimated 7% of the Victorian population were Chinese. Celestial Alley had also extended Chinatown Melbourne to Little Bourke Street, where Chinese businesses and cultural spaces were thriving. Miners who chose to remain in Australia after the gold supply had been sufficiently plundered turned towards new pursuits, becoming vegetable hawkers, merchants, laundry operators, or most lucratively, cabinet-makers.

This trend continued all the way until 1901 and the implementation of the White Australia Policy, which continued until the Racial Discrimination Act was passed in 1975.

Discrimination, Desertion and Desolation in Chinatown Melbourne

At the turn of the century, Chinatown Melbourne was at its peak. The seed that had once been Celestial Alley had tendrils extending from Swanston to Spring Street, with more roots winding into Little Lonsdale and Lonsdale Street.

Chinatown Melbourne, or the “Chinese quarter”, though still small in comparison to its American counterpart in San Francisco, was thriving, and already the largest in Australia.

Even when the White Australia Policy was implemented, Chinatown continued to boom. Unlike the previous racially-directed laws, which had been directed solely at Chinese immigrants, the new White Australia laws were not created to oust existing immigrants, but to deny new, all non-white immigrants entry. A large proportion of Victoria’s Chinese population chose to apply for certificates and documentation to allow them to remain in the country.

However, after the First World War, Australia and much of the world was in recovery. The mood had changed. Some 60,000 Australian men were killed during the War. 250 Chinese-Australians had enlisted as part of the Australian Imperial Force and 46 had been killed in action. The Great Depression was less than a decade away, but people were already starting to feel the pinch.

By the 1920s, Chinatown Melbourne was in decline. More and more businesses were closing their doors, families began moving out of Chinatown and into the suburbs, and older Chinese-Australians were packing up and leaving Australia.

The reasons for this were trifold. Firstly, there were cultural reasons. A few older Chinese-Australians, who had arrived as young miners, returned to their homeland when they reached old age so that they could be buried alongside their ancestors in accordance with their beliefs. As immigration was now so tightly controlled, new Chinese immigrants didn’t arrive to take their place.

Secondly, there were economic reasons. Factories replaced handcrafted furniture stores, so the cabinet-makers, who had once kept the most financially lucrative stores in Melbourne Chinatown, were put out of business. By 1932, only one cabinet-making business remained in Chinatown. Industrialisation turned inner Melbourne from a place people lived into a place where people worked, with families relocating to the suburbs or smaller towns.

Furthermore, import taxes had shot up exponentially. The merchants who imported goods from China, and the herbalists, fruit and vegetable hawkers and the laundrymen and women who relied on them could no longer afford the tariffs.

Thirdly, unemployment gradually became a glaring problem for all Australians, but racial discrimination made getting a job for Chinese-Australians next to impossible. Even the lowest paid jobs were highly sought after, so even when a rare gap in the market appeared, there was already a queue of white Australians who were prioritised above other races.

1970s to Now: Melbourne Chinatown Is Reborn

But it wasn’t all doom and gloom. By the 1940s, a few characteristic Melbourne Chinatown gems had appeared. The first and most notable was the invention of Dim Sim, the deliciously popular Chinese-Australian dumpling now served all over Australia. The chef, William Wing Young, created the recipe in his restaurant Wing Lee in 1945.

However, real positive change didn’t occur until after the White Australia Policy was lifted in 1975 and social attitudes altered.

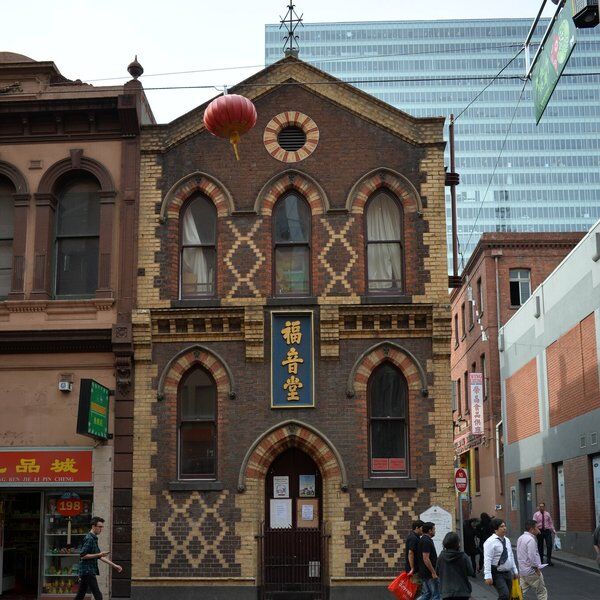

During the 1940s and ‘50s, the Gospel Hall, a small church on Heffernan Lane, was used for Christian worship by a small Cantonese-speaking minority. By the ‘70s, a speaker system had been introduced to accommodate the new influx of Chinese worshippers. In contrast to the previous Chinese immigrants to Melbourne, the new arrivals spoke Mandarin, and demand for a Mandarin-led service led to a deal being struck with the much bigger Wesleyan Church on Lonsdale Street.

Additionally, the new Chinese immigrants were a more varied demographic from those that preceded them in the 19th century. Far from being miners, the new arrivals were a mixture of businessmen, families, students and people seeking asylum after the demonstrations at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

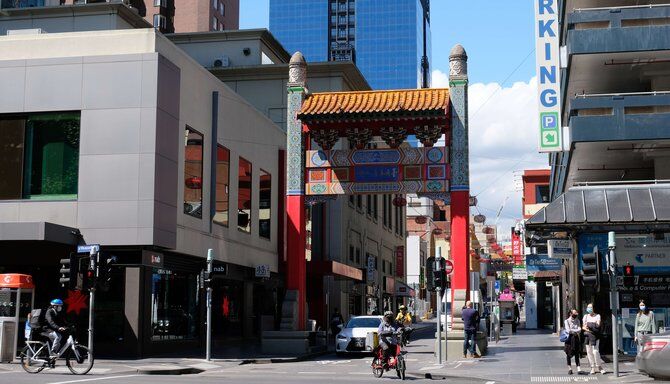

In 1976, a revitalisation scheme was commissioned to preserve the history and aesthetic of Chinatown Melbourne. This included adding suspended traditional Chinese arches to define the quarter from other Melbourne streets. By 1985, the arches had been transformed into permanent freestanding gateways.

To accommodate more tastes and to reflect the changing cultural background of the city, the shops and restaurants in Melbourne Chinatown also changed. The cabinet-makers of the past were gone, but in their place stood handsome buildings offering an ever-increasing array of imported items, services and eateries from all over China.

From 1986 to 1991, the population of those living in Australia but born in China more than doubled. According to the 2021 census, 27.6% of Australians were born overseas, of which 5.5% were born in China. Melbourne has the second largest population of Chinese-born residents with 8.3% born in China, second only to Sydney, New South Wales.

Things to See and Do in Chinatown Melbourne

These days, Chinatown Melbourne is a must-see on visitor’s bucket lists. From incredible eateries to the fascinating Chinese-Australian museum of Australia, there is something for everyone to experience - find out more below.

Best Asian Restaurants in Melbourne

Home of the Dim Sim and truly spectacular eateries, Chinatown Melbourne is a paradise for lovers of Asian-Australian cuisine. Finding the best restaurants in Chinatown Melbourne will vary considerably depending on your tastes, although we think you can’t go wrong with paying Flower Drum a visit.

Tax-Free Shopping

Perhaps paradoxically, many tourists to Melbourne flock to Chinatown in Melbourne to visit the tax free shops. When you think about it, this is a great marketing tactic: tourists will, of course, want to see Melbourne Chinatown and what do tourists love more than shopping? Discounted shopping, of course!

Museum of Chinese-Australian History

Right in the heart of Chinatown, the Museum of Chinese-Australian History (colloquially called The Chinese Museum) is a treasure trove of Chinese immigration history in Australia. It’s also where the world’s largest dragon, Dai Loong, lives when he isn't being paraded around during the Chinese New Year, so be sure to stop and pay him a visit.

Head’s Up: Dai Loong is HUGE! Eight people are required to keep his head up!

Hidden Bars

Keep your eyes peeled while wandering through Melbourne Chinatown’s many alleys. Seemingly ordinary doors conceal incredible hidden bars and eateries, mostly only known to locals and the most frequent visitors to the quarter.

Heritage Trail

Launched in 2015, the Chinatown Melbourne Heritage Trail allows visitors to meander through Chinatown and learn about its history through a series of plaques.

Chinatown Film Festival

Held annually, the Melbourne Chinese Film Festival is a not-to-be-missed event held in Chinatown Melbourne. This is where you can see new and upcoming Chinese language films, both from mainland China and other parts of the world.

Discover More about Chinatown Melbourne with CityDays

Ready to discover more of what Melbourne has to offer?

CityDays have FOUR treasure and scavenger hunts in Melbourne to choose from, all of which combine the fun of an escape room with the historic facts and whimsical trivia of a walking tour!

For those interested in exploring Melbourne’s Chinatown, check out our Frozen Idols, Shifting Walls route.

Take the stress out of planning your visit to Melbourne and book your adventure today!

Not visiting Melbourne this time? Don’t worry, you’ll find us all over the world.