Where there once was an ever-changing, hazardous estuary surrounded by marshland, a heavily industrialised port has now sprouted. Today, Dublin's Docklands are a hub of social connection, tech innovation, sports, food, history and culture. Global businesses such as Google, Twitter, LinkedIn and more than 600 others all have homes on the Liffey’s banks.

So how did it all start?

Obstacles to overcome

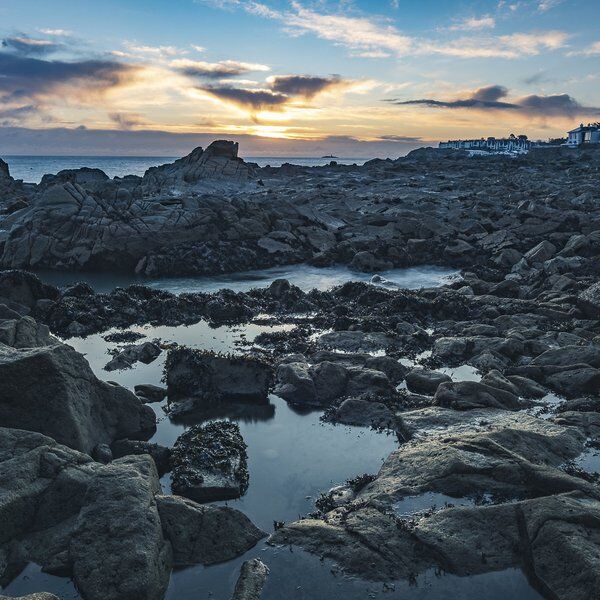

For centuries the official port of Dublin was not near the mouth of the Liffey, but was actually situated near Christ Church Cathedral, several kilometres inland. There were many reasons for this, most of which came from the estuary's perilous geography which presented a bottleneck to any major development of the area. While trade routes had been established, the Bay was littered with shipwrecks and lost cargo dating back to the Vikings, and much of what is now the Docklands was wholly underwater.

The lands either side of the Liffey were swampy and fickle, resistant to substantial development and under-utilised; the shifting sands of the estuary mouth resulted in a sandbar whose deceptive and changeable form had caught multiple ships off-guard as they approached the river. Heavy silt build up on the Liffey's bed presented issues for vessels even once they navigated into the estuary. For Dublin's trade to evolve alongside that of other European cities, work was needed.

This work was masterminded and spearheaded by John Beresford in the C18th. Beresford proposed a massive overhaul of the Docklands area - an overhaul that would see an evolution not just of its administrative and economic function, but would forever change the city's landscape. His plans were met with controversy and sometimes violent objections, but that's a tale for another day.

Taming the Estuary

Beresford's plans for economic transformation could not come to fruition without first making the estuary into a useable, fixed form - one that could sustain the diversity and scale of industry and operations that he envisioned. While the erection of Customs House to shift political and administrative functions to the new Port area was a significant milestone in setting things in motion, it was not enough: Nature still had to be overcome.

The undertaking to tame both the banks and sandbar was a staggering engineering operation that saw the estuary's coast locked into a stable form. The first undertaking was the South Bull Wall, or Great South Wall. Beginning construction in 1715, it was not finished until 1795. At a total length of 5km, 4km of which extends into Dublin Bay, it has withstood centuries of punishment since the early C18th. At the time of its completion it was the largest seawall in the world, and remains one of the longest in Europe even today. It was mirrored by the equally remarkable and newer Bull Wall which extends 3km into the Bay and is responsible for North Bull Island and nearly 5km of beach.

The Walls helped fix the shifting sands in place and enabled huge land reclamation projects to secure the estuary banks and transform miles of marsh into exciting potential.

The Diving Bell

So with the landscape more or less locked into place, how was the Port itself tamed? It's easy to look at the remarkable effects of the Walls as they stand now, but perhaps more interesting still is how they came to be erected. The Walls alone would hold back changes in the future, but countless hands were needed for their construction, and on-going maintenance required to prevent the estuary bed from building up once again.

Evidence of the ingenuity involved in clearing the Port can be discovered in the shape of the tiny Diving Bell museum in the Docklands, so named because it is contained within an authentic diving bell that was used as part of the development operations. It was the fabulously named Bindon Blood Stoney, a pioneering engineer in the Port's development, that realised the potential of the Bell for works in the C19th. The Bell, in combination with huge cranes that could manoeuvre several hundred-tonne concrete slabs into place, and the men working in and on those machines created the Port's foundations.

A deeply unpleasant experience, the 13m tall, 90 tonne Diving Bell was lowered underwater with a small group of passengers to work on the Liffey bed. With pressurised air pumped into the dome and the weight of the estuary overhead, the workers were tasked with clearing away silt, land and debris as part of foundational engineering works.

The work scarcely became more easier over the decades that followed. Dark, claustrophobic and wet, mud was diligently dug out and taken away to deepen the Port's bed. Even once the bed had been secured, it was still necessary for men to go down and prevent build up of silt and debris. The bell was in operation from 1871 until 1958.

The Docklands Rise

Once the estuary had been defined and passage secured, work towards the Docklands economic rise began in earnest.

As the Port became more trafficked, its significance grew substantially. No longer just an inconvenient divide between Dublin's people, it became a heartland for industry and – of course – work. People flocked to the area for jobs. Reclaimed land offered real estate for new industries as well as old, and previously untouched land was used for dock worker housing. And when space was needed for warehouses and factories, those houses were knocked down to make space resulting in an ever-increasing sprawl that spread along and away from both sides of the estuary.

Between the perfect blend of jobs and homes, other areas of Dublin that had once supported large populations began to decline as the Docklands grew. The once-fashionable heart of Mountjoy Square in the north for example experienced a predicable decline due to its immediate proximity to increasing traffic and the wastes of industry. This in turn led to many wealthy families moving the south shore and doubtless contributed to the explosion of Ringsend becoming the new Place To Be.

Following the construction and opening of Butt Bridge in 1879, the people of the two shores could begin to travel more easily. This contributed greatly to the eventual absorption of Pembroke township into Dublin City in 1930 as well as further accelerant to existing industries.

Present Day

Sadly the Docklands were left to decay over many decades following their initial rise, an almost inevitable consequence of modernisation, new industries, and mobility which can be seen in many major Port cities. In the 1990s, however, a new project was undertaken to revitalise the area as a hub for entirely new businesses and tourism. The impact to the area has been significant with global tech giants leaping at the opportunity to secure a footing in the regenerated area, and new residences and water sports all finding new homes. New infrastructure sees the area more connected than ever with new hotels, museums, and performance spaces giving tourists a fantastic opportunity to explore a long-overlooked part of Ireland's capital.

Want to learn more about Dublin and see some of it's secret & hidden sights? Check out our Dublin Treasure Hunts, puzzle-filled urban adventures lead you through city highlights and best-kept secrets. You'll actively engage with your surroundings to unravel the clues sent directly to your phones. Take optional breaks at great cafes & pub stops and enjoy the city's finest.