Nestled in Singapore’s most populous neighbourhood, Hougang, lies a little-known landmark known as Japanese Cemetery Park. Its history is a remarkable one: from its early days as a final resting place for shunned 19th-century Japanese sex workers to its recent revival and rescue in the 1980s, Japanese Cemetery Park is a lasting reminder of the tumultuous history between Singapore and Japan.

Today, Japanese Cemetery Park receives fewer visitors than its more famous counterparts but its beauty and historic legacy are enough to rival even major tourist destinations in Singapore.

Read on to find out more…

The History of Japanese Cemetery Park

The history of Japanese Cemetery Park begins with three Japanese brothel owners, Futaki Takajiro, Shibuya Ginji and Nakagawa Kikuzo, who lived in Singapore during the late 19th century.

Together, the brothel owners sought permission from the British Government to establish a Japanese cemetery for deceased destitute Japanese sex workers in 1891. Fukaki Takajiro, who was a rubber plantation owner as well as a brothel owner, donated 7 acres (2.8 hectares) of his plantation land to develop into the cemetery and the British approved of the request the same year.

In the days, months and years that followed, the Japanese cemetery slowly filled with the bodies of girls, men and women, hundreds of miles from their homeland - but how did they come to be there and who were they? Keep reading to find out.

From Malay Street to Japanese Cemetery Park: The Story of The Karayuki-San of Singapore

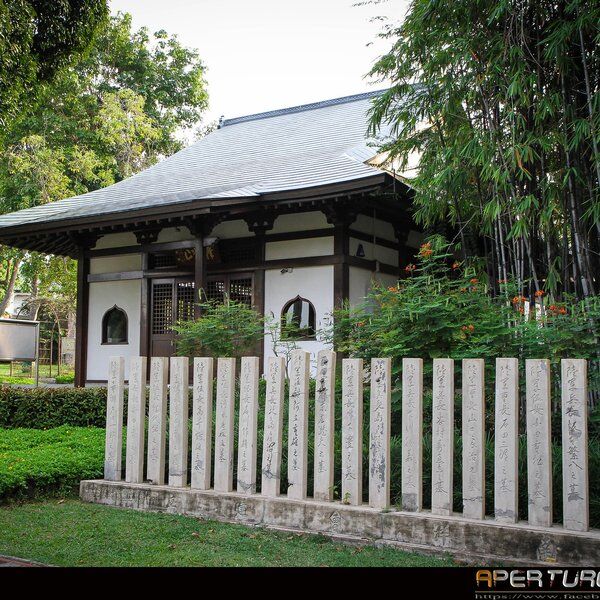

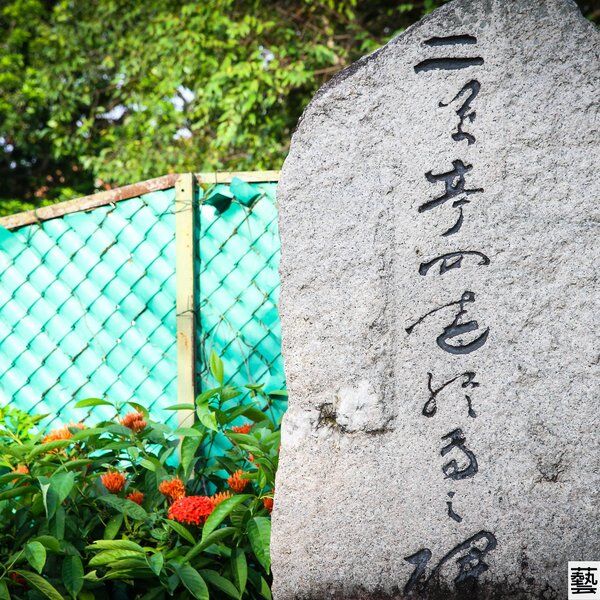

Little more than tiny stone stubs in the ground, the oldest graves in Japanese Cemetery Park commemorate some of Singapore’s deceased Japanese sex workers.

When Singapore was established as a Free British Trading Post in the early 19th century, Singapore experienced a population boom. European soldiers, bureaucrats and merchants flocked to Singapore, and mass cheap labour arrived in the colony from China and India. The result was that within a decade, Singapore’s population had grown exponentially and was over 80% male-dominated.

In a bid to ”assuage” the overwhelming number of men experiencing sexual frustration and a lack of social order, the British Government tried a radical new policy: legalising sex work.

As a result, young girls from poor areas of China and Japan, often from famine-affected prefectures, were ‘imported’ to Singapore.

The way in which girls were sent to Singapore varied: some desperate parents sold their daughters, other girls were coerced or tricked into contracts whereby their passage to Singapore was paid for, only to be told on board the kind of work they would be doing and that they were expected to pay back their ’loans’ through sex work on the other side. Many of the girls were between the ages of 13 and 15.

Just as Chinatown and Little India had become ethnic enclaves within the colony, a Japanese enclave sprung up around Hylam, Malabar, Malay and Bugis Streets, displaying storefronts of Japanese restaurants, doctors, bankers, merchants and shopkeepers.

By 1877, there were two documented Japanese-owned brothels on Malay Street (now Middle Street) with 14 workers. By 1909, there were 109 all over Singapore.

So many Japanese girls and women were sent to Singapore as sex workers that they were allocated a nickname in their native language: “Kurayuki-san” or “Women-who-went-overseas”.

Terrible stories about the girls’ experiences have emerged over the last century, some of which have been relayed by elderly women recalling their past experiences. Some of the harrowing tales include auctions for taking a girl’s virginity, girls being sold for between 1 and 2 thousand yen to pimps, the spread of debilitating venereal diseases and countless suicides through opium overdoses.

The sex trade in Singapore was so lucrative that it’s believed that women and girls were the third biggest export for the Japanese economy, just behind silk and coal. By 1921, however, the Japanese sex trade had started to decline.

The Japanese Consulate General in Singapore banned Japanese brothels, and many were repatriated to Japan. Those who weren’t moved to other parts of Malaya (now Malaysia) or continued to work as sex workers in secret.

For the Japanese girls and women who didn’t survive to tell their stories, however, they have been laid to rest in what is now Japanese Cemetery Park in unmarked graves so as not to humiliate their families. Some reports suggest that their graves are even placed facing away from the direction of Japan as a mark of their shame, although these claims have not yet been confirmed by historians.

A Place to Rest: Japanese Cemetery Park and World War II

Even after the decline of the Japanese sex trade, plenty of Japanese businesses continued to flourish in Singapore and when their Japanese owners, workers and customers passed on, they joined the young girls and women in the Japanese cemetery.

When Japan took control of Singapore in 1943, the cemetery was used to bury any deceased Japanese soldiers and citizens killed on the battlefield or through illness - this time with more opulent and named tombstones. By the end of the war, however, many more bodies needed to be buried.

After the war, the British authorities repatriated all Japanese citizens living in Singapore - a policy that disallowed Japanese people to return to the country until 1951 when the Official Peace Treaty was signed between the two nations. Japanese Cemetery Park lay dormant between the intervening years but was left intact, despite the animosity between the two nations.

Afterwards, the Japanese Consul General, Ken Ninomiya, was put in charge of locating the remains of Japanese soldiers in Singapore, in the hopes of repatriating the ashes to Japan where they could be mourned by loved ones. However, this plan was abandoned in favour of burying the remains in Japanese Cemetery Park, a ready-made site with enough space to accommodate the fallen, complete with a shrine erected by Japanese soldiers during the war.

In 1969, following Singapore’s declaration of Independence, the Singapore government handed control of Japanese Cemetery Park over to the Japanese Association, which continues to oversee the maintenance of the cemetery.

Interestingly, during the 1980s, the Japanese cemetery was ‘converted’ into a park to save it from demolition or removal. Singapore had emptied its own graveyards and cemeteries to make space for the tall, sparkling high-rise buildings - but the Japanese government found a caveat. If the cemetery was deemed a public space, like a garden or park, then the cemetery would be allowed to remain.

Japanese Cemetery Park in Popular Culture

While Japanese Cemetery Park hasn’t received much attention in comparison to other Singapore landmarks, it has featured prominently in Japanese popular culture.

The book “Midnight Express”, written in the 1970s by the prolific non-fiction author Kotaro Sawaki features Japanese Cemetery Park during the author’s visit to Singapore. “Midnight Express” was a best-seller in Japan, owing to the author’s rich descriptions of other nations on his journey from Hong Kong to London.

While in Singapore, Sawaki visited the cemetery and read a book in the shade of a tree - possibly one of the original rubber trees that had been planted before the plot of land had even been used as a cemetery!

See and Do at Japanese Cemetery Park

Today, Japanese Cemetery Park is a serene space that welcomes reflection and a pause from the hustle and bustle of the city.

Visitors are welcome to visit the Prayer Hall - built in 1986 - wander among the graves or admire the incredible bougainvillaea archways that line the path.

Some of the graves to keep an eye out for include Singapore’s first Japanese resident, Otokichi Yamamoto, the commander of the Southern Expeditionary Army Group, Hisaichi Teruachi and the park’s first caretaker, Weng Ya Zhang.

Finally, although Japanese Cemetery Park is a designated public space, remember to show respect while taking a look around by not touching the memorials and keeping noise levels to a minimum.

Discover More of Singapore With CityDays

Ready to discover more of what Singapore has to offer?

CityDays have a brand new treasure and scavenger hunt in Singapore which combines the fun of an escape room with the historic facts and whimsical trivia of a walking tour!

Take the stress out of planning your visit to Singapore and book your adventure today!

Not visiting Singapore this time? Don’t worry, you’ll find us all over the world.