Discover Millbank Prison

Positioned on the riverbank near Vauxhall Bridge in Westminster, Millbank Prison was much more than just a correctional facility. Originally conceived as Britain’s National Penitentiary, it opened its doors in 1816 and served as a holding station for those thought capable of reform—offering five- to ten-year sentences as an alternative to being shipped off to Australia. But as the days went by, the building’s many quirks and challenges soon told a different story. The prison’s name hails from an old mill once owned by Westminster Abbey.

Constructing Millbank Prison: Bentham’s Panopticon

Millbank Prison was commissioned by the British government, following the passage of the Penitentiary Act of 1779. This act was co-authored by philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s brother, Samuel Bentham, and reformers like John Howard and Sir William Blackstone.

It wasn’t until 1799, that a marshy plot of land near the Thames was chosen for the project and parliament had approved Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon design. The Panopticon concept meant the inmates would be arranged in a circle around a central watchtower.

A Revolving Door of Architects

However, in 1812, the plan for a perfectly round prison was shelved, leading to a competitive search among 43 design proposals. The winning blueprint was designed by William Williams. However, constructing a massive, state-of-the-art penitentiary on damp, marshy ground wasn’t without its challenges.

After Williams couldn’t deliver, the reins were taken over by Thomas Hardwick, who stepped down in 1813, followed by John Harvey, and finally, Robert Smirke. Smirke not only steered the construction to completion in 1821 but also introduced an ingenious solution: a concrete raft foundation that tackled the marsh’s mischief head-on.

Final Concept

The final design was hexagonal as opposed to the original circular Panopticon design. It featured a circular chapel at its heart, encircled by a three-storey hexagon that housed the governor’s quarters, administrative offices, and laundries. Radiating from this core were six pentagonal cell blocks, each with its own cluster of small courtyards—complete with a central watchtower to keep a keen eye on the inmate labour happening below.

The outer corners of these blocks had tall, Martello-like towers that not only added an imposing silhouette to the structure but also cleverly concealed staircases and water-closets. And while each cell came with a small window facing the courtyard and basic furnishings like a washing tub, a wooden stool, and even a Bible or hymn-book, the design was more about discipline than comfort.

Interesting Fact: Smith’s technique was the first of its kind in Britain since Roman times.

History of Millbank Prison

The First Inmates

On 26th June 1816, and the very first batch of prisoners arriving at Millbank were all women. Just a few months later, in January 1817, the male inmates started trickling in. By the end of that first year, the numbers were modest—about 103 men and 109 women.

Fast-forward to late 1822, and the prison was bursting with roughly 452 men and 326 women. For those considered capable of mending their ways, sentences ranging from five to ten years were offered as a kinder alternative to the dreaded transportation to Australia.

Living Conditions and Disease

Life inside Millbank Prison was harsh. Inmates faced severe restrictions—minimal rations, barely five minutes of exercise daily, and a rule of absolute silence for the first half of their sentence. Non-stop tasks like turning a screw until it clicked and relentless treadmill work were the order of the day.

Whatsmore, the marshy, damp location did little to help the prisoners’ health, especially when paired with a meager diet that left them with little resistance to disease. One inmate, Henry Harror—jailed for horse theft—ended up so emaciated that his remains were later described as nothing more than skin stretched over bone.

By 1818, health concerns had become so pressing that Dr. Alexander Copland Hutchison was roped in to oversee inmate care. Unfortunately, by 1822–23, a nasty cocktail of dysentery, scurvy, and other ailments—mixed in with a dash of depression—swept through the halls.

The conditions were so dire that the authorities had to temporarily evacuate the prison; the women were set free, and the men were moved to prison hulks at Woolwich, where, thank goodness, their health began to improve.

Design Disasters and Escape-ades

Millbank’s labyrinth of corridors was so twisty that even the wardens sometimes lost their way. To add insult to injury, the ventilation system had a quirky side effect: it let sound travel far and wide, meaning that prisoners could easily chat (or plot their next escape) from cell to cell. With annual running costs soaring to an unsustainable £16,000, it was clear that not everything was going according to plan.

There was also the odd escape attempt over the years. One of the most infamous was that of two clever characters, Meggs and Carey. They left behind dummies (complete with nightcaps!) in their beds, crawled through a ventilation hatch, scaled a wall, donned soldiers’ uniforms, and even flagged down a cab—all before being recaptured the next day.

Changing Roles

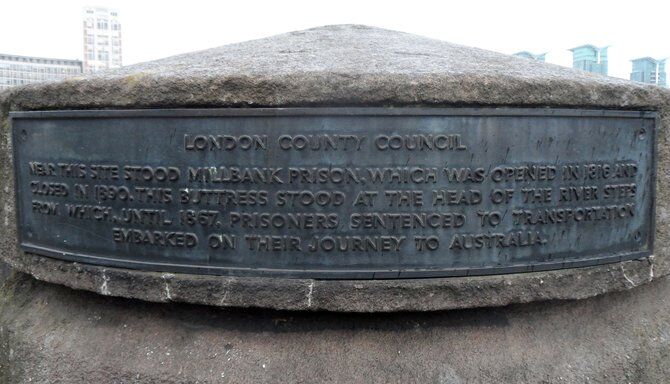

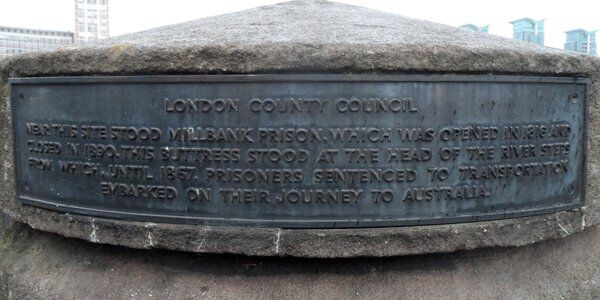

By the early 1840s, Millbank’s grim conditions and confusing layout prompted Parliament to rethink its role. In 1843, a new act officially downgraded the prison from a state-of-the-art penitentiary to a holding depot for convicts awaiting transportation.

Suddenly, instead of offering a chance at reform, Millbank became the staging ground for those bound for Bermuda, or Norfolk Island and Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) in Australia. Convicts would spend about three months here before being loaded onto transport ships.

In fact, during its transportation heyday, around 4,000 convicts per year were sent off to the other side of the world. The facility even earned a cheeky bit of prison slang—some say “pom” (short for “Prisoner of Millbank”) came from this very practice!

Closure and Demolition

As the 19th century marched on, the function of Millbank continued to evolve. After the mass transportation of convicts wound down by the late 1860s, the prison shifted roles once again, eventually becoming a local prison and, from 1870, a military one.

By 1886, Millbank had finally ceased holding inmates, and it closed its doors in 1890. The demolition process began two years later and continued sporadically until the early 20th century.

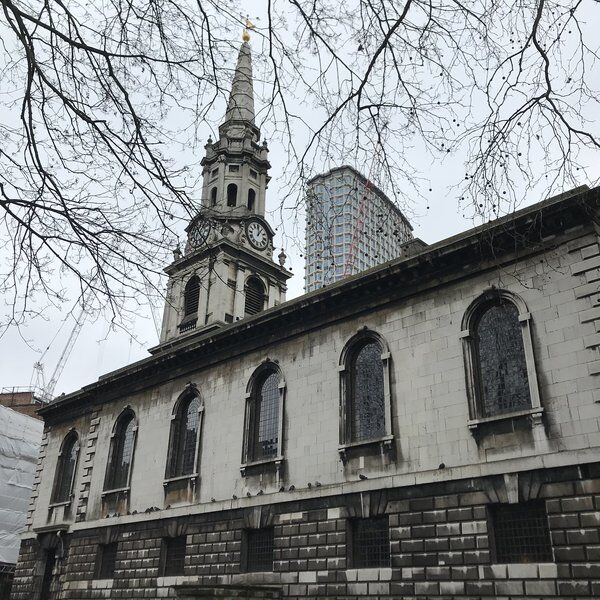

But here’s the twist: while the prison’s physical structure was dismantled, its legacy lives on. In 1899, during the demolition, sugar magnate Sir Henry Tate donated his art collection and a hefty sum to fund a new gallery. That’s right, out of the ruins of Millbank emerged what we now know as Tate Britain.

Millbank Prison in Pop Culture

The gloomy corridors and architectural oddities of Millbank Prison have inspired countless writers and creators over the years. Here are a few highlights:

- Charles Dickens gave a nod to its grim atmosphere in his classic novel Bleak House, painting a vivid picture of its stark surroundings.

- Henry James found the prison’s eerie charm central to the emotional core of The Princess Casamassima.

- Arthur Conan Doyle even had Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson brushing past its imposing structure in The Sign of Four, while another Conan Doyle tale, The Lost World, cheekily mentioned it as a final resting place.

- In more recent times, modern works like Sarah Waters’ Affinity and the horror podcast The Magnus Archives have woven Millbank into their narratives.

Visiting Millbank Prison in London Today

Even though the intimidating red-bricked walls of Millbank Prison are long gone, it is still possible to visit the site, which is now home to a housing estate and the celebrated Tate Britain.

Tip: If you stroll along John Islip Street toward Cureton Street, you might just spot the lingering traces of the old prison moat, now cleverly repurposed as a clothes-drying nook or allotment space for local residents.

Explore Beyond Millbank Prison with CityDays

Ready for more adventures? At CityDays, we believe that history, art, and fun go hand in hand.

Beyond exploring iconic sites like Millbank Prison, we offer exciting scavenger hunt and treasure hunt tours across the city.

Answer riddles, solve puzzles, and learn more about London’s 2000-year-old history in a new and interactive way!

Take the stress out of planning your visit to London and book your adventure today!

Not visiting London this time? Don’t worry, you’ll find us all over the world.