Sandwiched between the historic grandeur of St Paul’s Cathedral and the site of the present London Stock Exchange, Paternoster Square is an urban development in Central London with a fascinating ecclesiastical and literary past.

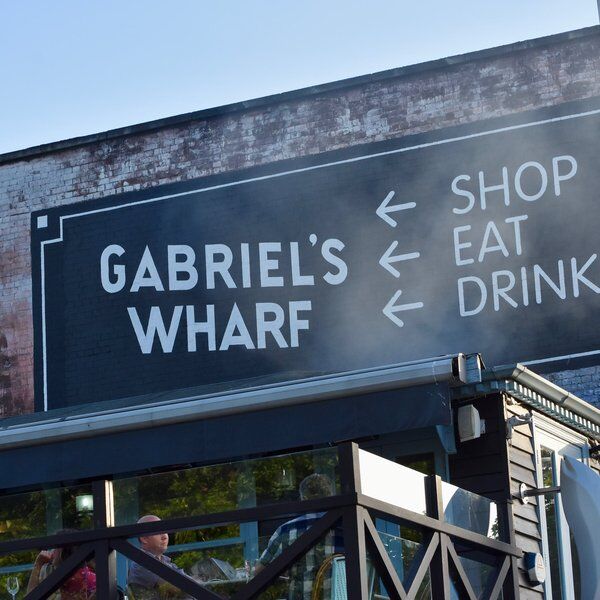

Frequently overshadowed by its neighbours, Paternoster Square is now home to plenty of shops, restaurants and three curious monuments, while its past is one that combines 12th-century monk chants, 16th-century literary moguls and even the Brontë sisters…

History of Paternoster Square

At just two decades old, the refurbishment of Paternoster Square makes it look deceptively new.

But the first clue to Paternoster Square’s true age lies in its name.

When the building of the original St Paul’s Cathedral was completed in the 12th century, it was considered a masterpiece. It was 585ft (178 m) long, making it the third-longest church in the Christian world at the time.

It’s believed that the name of Paternoster Square comes from the monks, friars and other clergymen who would walk in procession to St Paul’s church along Paternoster Row, reciting the Lord’s Prayer in Latin as they did so. England was Catholic at the time, and so the prayer was said in Latin, the first words being ‘Pater Noster’ or, in English, ‘Our Father’.

During the Middle Ages, the monks of St Paul’s and Paternoster Row had the company of salespeople who peddled religious books and materials such as paternosters - rosary beads used by illiterate monks for counting (they had to recite the Lord’s Prayer 30 times, three times a day).

By the 16th century, shops selling religious items were replaced by merchants selling silk, lace and other expensive fabrics to the nobility and gentry. Paternoster Square was notorious for its high-quality imported goods, and locals often complained that there was hardly any room to walk due to the popularity of the shops.

But another change was on the horizon, this time born out of disaster. In 1666, a fire in a bakery on Pudding Lane set the city of London ablaze for four days. It became immediately apparent that the damage was catastrophic, not least because London’s most-impressive building was missing from the skyline: St Paul’s Cathedral and everything surrounding it had been reduced to ashes.

Although the Great Fire of London ripped through the city in just a few days, the rebuilding of London was to take far longer.

After the charred debris had been cleared from St Paul’s and its surrounding area, a new industry emerged that would change the legacy of Paternoster Row for hundreds of years: publishing.

Publishing and Paternoster Square

'The Row, as it is called by way of pre-eminence, is the nucleus of the literary neighbourhood ... How the literary man delights to haunt this place.'

By the end of Elizabeth I’s reign, literacy rates in England were increasing: an estimated 30% of men and 10% of women in England could read and write. The books available in Elizabethan England were mostly ecclesiastical - the bible had been translated into English for the first time in 1526 by William Tyndale - although DIY books for gardening, cooking and husbandry were becoming increasingly popular.

By the 18th century, Paternoster Row was almost entirely made up of publishing houses and bookshops. Nicknamed “The Row”, the buildings of book purveyors were furnished with symbolic signs instead of numbers - England would have to wait for Napoleon to implement the house number system in Paris in 1805 before it became commonplace.

The first “novel” written in English was published in Paternoster Row by William Taylor of The Ship and Black Swan publishing company in April 1719. Its contemporary title is probably familiar to you - Robinson Crusoe, by Daniel Defoe. Taylor later sold the publishing house to a Bristol man, Thomas Longman, another name which might ring a bell - he was the original Longman of Pearson Longman, which continues to publish books to this day.

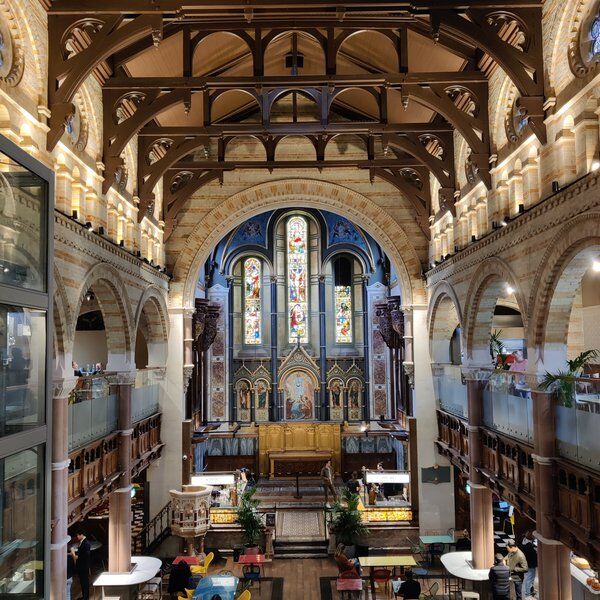

The Chapter Coffee House

In the 1670s, London was entering a phase of renewal and modernity. After years of civil war, a catastrophic fire, plague and general misery, Londoners were witnessing the rebirth of a city that was growing bigger and better every day.

From the ashes emerged new, better-designed dwellings of stone or brick, thatched roofs were replaced with tiles or slate. The air around the docks became filled with the fresh aromas of new herbs and spices, the boats laden with full-bodied coffee beans and tea leaves.

As a result, so-called ‘coffee houses’ popped up all over the city. Merchants, intellectuals, and writers flocked to them, realising the coffee house's potential as a less sordid venue for meeting and conducting their affairs than the pubs and inns they were accustomed to.

Around 1672, the publishing houses of Paternoster Row got a new neighbour - a coffee house of its very own, aptly named The Chapter. Its patrons include writers such as Samuel Johnson (the author of the first English dictionary) and Thomas Chatterton, a Bristol-born writer who Keats would later describe as ‘the purest writer in the English language’.

The Chapter was famous in the city for its bookish clients and many newspapers, periodicals and pamphlets which customers could peruse after purchasing a hot drink. It eventually received a street number, its address being 49-50 Paternoster Row. The Chapter closed its doors as a coffee house in 1854 and subsequently became a tavern.

Books and The Blitz

In 1940, London and the rest of the United Kingdom encountered fresh terror and destruction. The Blitz, a German bombing campaign during WWII, began in 1940 and killed an estimated 43,000 people. Towns and cities were reduced to cinders.

Famously, St Paul’s Cathedral remarkably escaped extensive damage. But its neighbouring street, Paternoster Row, wasn’t quite so lucky. 100,000 bombs fell on London during the Blitz, many of which fell directly on what is now Paternoster Square.

An estimated 5 million books were destroyed, along with the publishing houses, bookshops and other buildings. England’s literary trades moved to new premises in Fleet Street and other venues around London, and for a while, Paternoster Row was deserted. The Chapter, the famous coffee house turned tavern, was also destroyed.

Postmodern Paternoster Square

After WWII ended, London was once again gearing up for drastic changes. Rebuilding was taking place all over the country, but what to do with Paternoster Row remained a contentious subject.

By 1956, the Corporation of London engaged an architect, Sir William Holford, to redesign the then-desolate patch of land north of St.Paul’s. Holford’s vision was to modernise the area, improve traffic and create a space that was sympathetic to Christopher Wren’s masterpiece monument. However, it was not to be.

The results, after many rewrites and changes, were disappointing. The new Paternoster Square beyond the small remaining sliver of Paternoster Row was instantly despised. In 1961, when the project was complete, Londoners were left scratching their heads at the ugly office blocks that contrasted horribly with St Paul’s Cathedral.

One Londoner in particular was horrified by Paternoster Square. In the 1980s, the then Prince of Wales (now King Charles III) made his opinion very plain at an annual dinner of the Corporation of London’s Planning and Communications Committee:

“You have to give this much to the Luftwaffe. When it knocked down our buildings, it didn’t replace them with anything more offensive than rubble. We did that.”

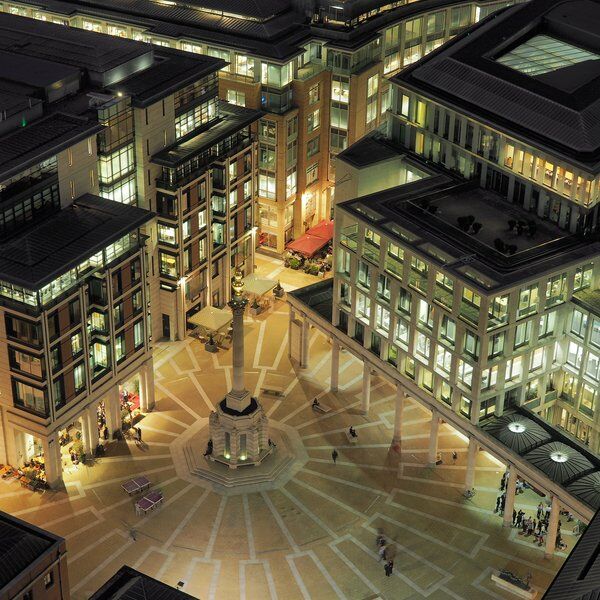

Ouch. It wasn’t until 1996 that planning permission was granted to Sir William Whitfield to redesign Paternoster Square, which reopened in 2003 looking very much as it does now.

Paternoster Square Monuments

There are three major monuments in and around Paternoster Square. Details about them can be found below.

Paternoster Column

The Paternoster Square column is the tallest and most obvious monument in Paternoster Square. The column is designed in a Corinthian style and made of Portland stone, crowned with a gold leaf flaming copper urn.

It was designed by William Whitfield’s architectural firm, Whitfield Partners and was inspired by Inigo Jones’ similar columns that were destroyed during the construction of St.Paul’s.

Interestingly, the column also acts as an air vent for the car park below.

The Shepherd and Sheep

The Shepherd and Sheep sculpture, also known as the Paternoster, was created by Elizabeth Frink in 1975. It is made of bronze and is a historical reminder to present-day visitors that Paternoster Row once led to one of England’s largest meat markets, Newgate Market.

Interested in London’s artistic and agricultural past? Read about Shepherdess Walk in Hackney here!

Temple Bar

Last but by no means least, the entrance to Paternoster Square is made unmissable by the grand gateway leading from St Paul’s Churchyard. The only surviving gateway to the city, it was designed by Christopher Wren and originally stood at a junction between Fleet Street and the Strand.

Remarkably, it wasn’t destroyed during the Great Fire of London or the Blitz, although it has seen its fair share of grisly London history; the decapitated heads of traitors were displayed on iron spikes there during the 18th century.

One reason why Temple Bar gateway survived WWII is that it was deconstructed in 1878 to make room for traffic. It was purchased ten years later by a wealthy socialite in Hertfordshire, who had it rebuilt brick-by-brick at her estate. In 2001, the newly-formed Temple Bar Trust paid for the cost of its removal and reconstruction at Paternoster Square where it was opened by the Lord Mayor of London in 2004.

The Best Way to Visit Paternoster Square

The best way to discover more hidden gems around Central London is to take your time and, ideally, have a pre-planned route that takes you past all the noteworthy nooks and major monuments. We can help you there!

The City combines the fun of an outdoor treasure hunt with the historic facts and whimsical trivia of a walking tour.

Starting just around the corner from Paternoster Square, this trail will have you solving riddles, untangling puzzles and learning more about London’s 2000-year-old history in a new and interactive way - plus you get 20% off food and drink at a historic pub chosen by us!

Take the stress out of planning your visit to London and book your adventure today!

Not visiting Central London this time? Don’t worry, you’ll find us all over the world.