Discover St Bernard’s Well

Set deep in the valley, on the banks of the Water of Leith, and flanked by the leafy grandeur of Edinburgh’s New Town, St Bernard’s Well feels almost otherworldly. It's a place where ancient legend, Enlightenment-era architecture, and a dash of Mary Shelley come together to create one of the city’s quirkiest landmarks.

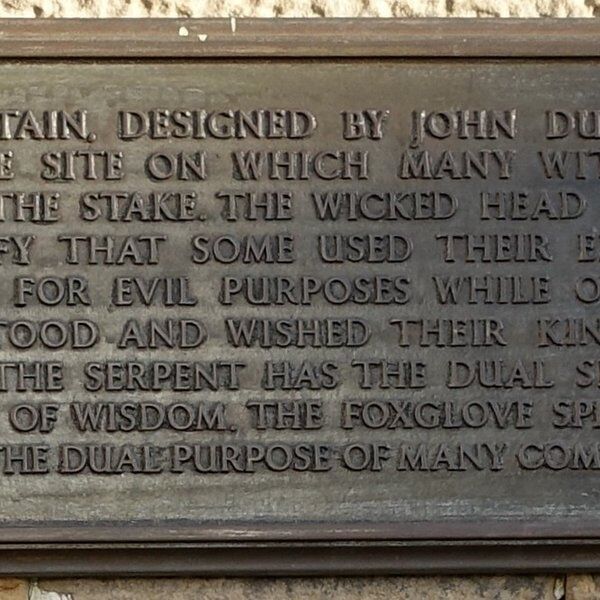

Forget your standard city fountain—this is a Roman-style temple, complete with Doric columns, a domed roof, and a statue of a Greek goddess. You’ll also find mossy staircases, decorative railings, and a plaque dedicated to William Nelson, the local philanthropist who saved the well from disrepair in the 19th century.

Oh, and that pineapple on top of the dome? It’s a symbol of hospitality—so consider it a very fancy way of saying “welcome.”

The Origins of St Bernard’s Well

The story of St Bernard’s Well begins with a bunch of schoolboys. Back in 1760, a group of lads from George Heriot’s School were out fishing along the Water of Leith when they stumbled across a spring bubbling up near the banks.

According to local legend, however, the well’s history goes back even further. The spring is named after St Bernard of Clairvaux, a 12th-century monk who is said to have lived in a nearby cave while preparing for the Second Crusade.

St Bernard supposedly discovered the spring and claimed it had healing properties—a divine pit stop for weary crusaders. By the late 1700s, word had spread: this wasn’t just any old water source—it was a miracle in a stream.

When Edinburgh Embraced Spa Culture

In the 18th and 19th centuries, spa culture was all the rage, and Edinburgh wanted in. Locals began “taking the waters” at St Bernard’s Well, braving the foul-smelling, sulphur-rich spring for the promise of better health.

Reports suggested it cured ailments ranging from digestive troubles or gout, to arthritis and bad moods—and even blindness if you believed the bravest drinkers. (Some claimed the water worked best when mixed with coffee, no less!).

One contemporary poet, going by the pseudonym Claudero, even wrote a glowing verse about it:

“This water so healthful near Edinburgh doth rise;

Which not only Bath but Moffat outvies…”

However, while some praised its miraculous effects, others were less than enthused about the taste. One bold critic likened it to “the washings from a foul gun barrel,” and another described a “hydrogen twang” you’d probably not want to bottle and sell. But hey, beauty’s pain, right?

To capitalise on the well’s growing popularity, a well house was built over the spring in 1789—though this wasn’t just any shed. Enter Alexander Nasmyth, a celebrated Scottish painter and designer, tasked with creating something spectacular.

Nasmyth’s Temple of Health

And spectacular it is. The structure that stands today is nothing short of a neoclassical delight: a circular, Roman-style temple modeled after the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy. It’s complete with ten Doric columns, a pineapple-topped dome (symbolising hospitality), and an inner chamber that oozes Enlightenment ideals.

Inside the temple stands a statue of Hygeia, the Greek goddess of health, watching over the spring in serene, marble silence. The original statue, made from Coade stone, was considered too large and eventually replaced in 1888 by a sleeker Carrara marble version sculpted by David Watson Stevenson.

A particularly fancy pump room hides beneath the statue, decked out in blue, white, and gold. It’s usually closed to the public, but if you’re lucky enough to step inside during open days, prepare to be dazzled by its ornate splendour—and maybe a whiff of its famously metallic scent.

Even the motto above the door gives a hopeful nudge: Bibendo Valeris—"Drink and you will be well." (Spoiler: probably not anymore.)

Lord Gardenstone and St Bernard’s Well

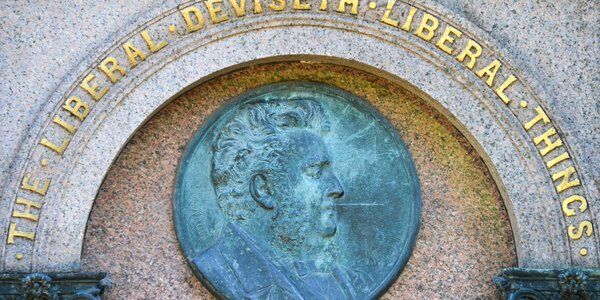

Much of what we see today is thanks to Lord Gardenstone, an eccentric Edinburgh lawyer and one of the well’s biggest fans. He bought the spring in the late 18th century and commissioned Nasmyth to create the iconic temple.

Gardenstone wasn’t just a man of odd bedtime habits (he apparently shared his sleeping quarters with piglets); he was also a progressive thinker and a passionate anti-slavery campaigner. He played a leading role in the famous 1778 case of Joseph Knight, which contributed to ending slavery in Scotland.

When it came to the well, Gardenstone took things seriously. He appointed a custodian, charged a penny per glass (half-price for children), and even encouraged visitors to take a brisk walk afterwards—partly to aid digestion, partly to keep the queue moving.

Victorian Fame, Frankenstein, and Football Clubs

St Bernard’s Well didn’t just charm the locals—it caught the imagination of some of the 19th century’s biggest literary names. Most notably, it earned a shoutout in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In Chapter 19, Victor Frankenstein himself remarks on the sights of Edinburgh:

“Arthur’s Seat, St Bernard’s Well, and the Pentland Hills... filled him with cheerfulness and admiration.”

Not bad company for a little spring in the woods.

Later, the well’s distinctive Doric rotunda even inspired the badge of the now-defunct St Bernard’s Football Club, who famously won the Scottish Cup in 1895. Healing powers or good footwork? We may never know.

A Whiff of Arsenic and a Dip in Popularity

By the mid-20th century, the magic had worn off. In 1956, health officials tested the water and made a rather unpleasant discovery: arsenic and other nasties had made their way into the spring. Not exactly the wellness tonic people were hoping for.

The well was closed, and over time, the structure began to decay. But all was not lost…

The Revival of St Bernard’s Well

In 2012, thanks to the Twelve Monuments Project led by Edinburgh World Heritage, St Bernard’s Well received a much-needed facelift. A whopping £232,000 was spent on the restoration, with everything from the mosaic ceiling to the golden pineapple on the roof given a fresh lease of life.

Today, the temple is normally closed to the public but opens on select days throughout the year for curious visitors who want to peek inside and soak up the vibes of Enlightenment Edinburgh (without actually drinking anything sulphurous).

Visiting St Bernard’s Well

First things first—don’t go expecting to bottle your own miracle tonic. The spring’s not in full-time operation anymore, and the well’s inner sanctum is mostly closed. But fear not! The outside of this architectural oddball is still a showstopper.

How to Find St Bernard’s Well

If you fancy getting up close and personal with Hygeia and her pillared perch, head to the Water of Leith walkway between Dean Village and Stockbridge. The west end of Saunders Street in Stockbridge is your easiest entry point.

When to Go Inside

For those who want to peek behind the proverbial curtain, the Dean Village Association opens the pump room to the public on the first Sundays of the month from April to July, and then most Sundays in August. It also throws open its fancy doors during Doors Open Day in September, part of a city-wide event that unlocks hidden corners of Edinburgh for curious minds.

Top tip? Bring a camera, a bit of historical curiosity, and maybe hold your nose just a little if the well’s doing its sulphuric thing. The water might not be the cure-all it once was, but the walk itself is a tonic for the soul.

Explore Beyond St Bernard’s Well with CityDays

So, you’ve soaked up the sights (if not the sulphur), admired the stately columns, and pondered whether Hygeia would have approved of your oat milk latte. What’s next? Well, if you're craving more quirky corners, hidden stories, and scenic strolls, CityDays has got your back.

Our scavenger hunts and treasure trail tours in Edinburgh are designed to show you the city in a whole new light—whether you're a lifelong local or a first-time visitor. Think clues, curious facts, team challenges, and loads of fun woven into the fabric of the city itself.

We’re also the go-to option for team-building events that ditch the boardroom in favour of secret gardens, winding alleys, and epic trivia battles. Whether you're bonding with colleagues or just fancy a competitive wander with friends, CityDays makes Edinburgh an open-air playground.

And we don’t just stop in Scotland—our adventures stretch across cities worldwide, offering the same mix of history, mystery, and hilarity wherever you roam.

Ready to play? Ready to explore? Let’s go!