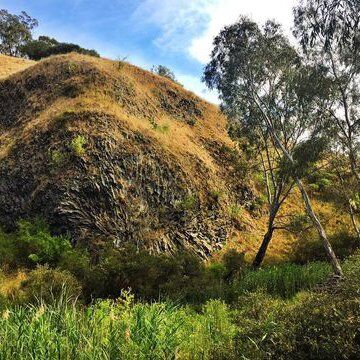

Organ Pipes National Park is part of a 121 hectare (300 acre) protected Aboriginal conservation on the traditional land of the Wurundjeri People. It is located on top of one of the world’s largest volcanic rock flows, which stretches around 350km from the edge of Melbourne to the western border of Victoria. For around 20 million years, volcanic activity was widespread in South-Western Victoria, although the lava covering the Organ Pipes parkland is a recent flow, only about a million years old.

Today, the easily accessible National Park features a popular hiking trail and bushwalk for Melbourne families and tourists. People flock to the Park for its breath-taking views and multiple geological features broadly categorised as the Organ Pipes, Tessellated Pavement, Rosette Rock, and Scoria cone. There are also native plants and lots of animals to spot whilst wandering through the beautiful cultural landscape.

What are the Organ Pipes?

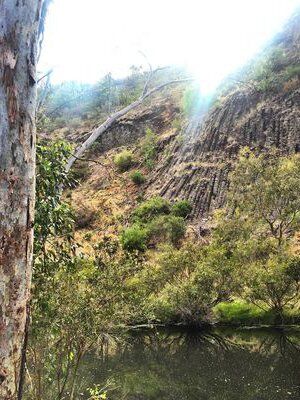

The National Park was established to conserve the native fauna and flora and to preserve the area's geological features. These include the impressive basalt rock formation situated 20 kilometres north west of Melbourne’s business area, the Organ Pipes, for which the park is named!

The towering basalt columns — that stretch up to 20 metres in height and look just as their name suggests — were formed about a million years ago when a mass of molten lava was ejected from volcanoes near what is now Sunbury and across the Keilor Plains. These plains are mostly flat, but for the deep valleys cut in them by the streams of Jacksons Creek. It was this slow cutting that ultimately exposed these tremendous geological structures, which now look just like organ pipes.

How were the Organ Pipes formed in the National Park?

As the lava cooled over several years the interior molten lava, commonly referred to as trap rock, fractured and caused shrinkage.

This shrinkage caused tension in the rock mass. Vertical (upward and downward) tension could be accommodated by the elastic molten rock beneath but horizontal tension could not be relieved and so the basalt cracked. The rock usually cracks in a hexagonal pattern (six sides), but columns with up to eight sides are found. The rock was still hot (about 400 °C (752 °F)) when the columns were formed. Further contraction took place as the rock lost its remaining heat; this was relieved by horizontal cracking, causing some columns to look like stacks of Dutch cheese.

What else can you see at Organ Pipes National Park?

Scoria Cone

The park's car park is situated on the remains of a weathered scoria cone. Around the time the larger volcanoes to the north were producing lava (800,000 to a million years ago) this cone ejected molten rock in a series of explosions, producing scoria. Scoria is brownish in colour and is filled with air-pockets.

Rosette Rock

Approximately 500 metres upstream of the Organ Pipes, (taking the Left River Trail) on the northern bank of the stream, is a large outcrop of overhanging basalt with a spiralling array of columns resembling the spokes of a giant wheel. This is known as the Rosette Rock formation and was formed by the radial cooling of a pocket of lava, probably in a spherical cave formed from an earlier lava flow.

Tessellated Pavement

Onwards, 300 metres past the Rosette Rock, is the Tessellated Pavement. These columnar basalt rock structures were formed by the same lava flow that makes up the Organ Pipes; however, in this instance the Jackson’s Creek has caused a tiled, or mosaic-like erosion — this time on the valley floor.

Due to the horizontal nature of the formation it is possible to walk and climb over the structure. Although, it has been determined that frequent access to the Tessellated Pavement will likely cause its deterioration.

Wildlife

Organ Pipes National Park authorities have reported a diverse range of wildlife in the area including:

- Birds

- Swamp Wallabies

- Eastern Grey Kangaroos

- Long-Necked Tortoises

- Eastern Bearded Dragons

- Red-Bellied Black Snakes

- Echidnas

- Bats

- Platypuses

The History of the National Park’s Wildlife

The area's earliest settlers were the Aboriginal Woiwurrung people who sought shelter, water and food along the Jackson Creek. They were farmers and hunters who harvested the natural products the Keilor Plains had to offer.

At the time the following species flourished:

- Kangaroos

- Dingoes

- Tigers

- Bandicoots

- Gliders

- Platypuses

- Cockatoos

- Kookaburras

- Quails

- Finches

- Hawks

There was also luscious vegetation, with grass lands and plenty of plants with flowering blooms.

All this changed however in the 19th century when Europeans began settling in the area. These people were primarily responsible for introducing several species of exotic plants (boxthorn hedges for fences and oaks, willows and pine, simulating an ambiance of their homeland) and animals. They did this because they believed the landscape to be drab and filled with strange animals. Subsequently, kangaroos were culled and rabbits and other furry animals were killed for their pelts.

These dramatic changes to the National Park’s environment had disastrous effects on the native flora and fauna:

High artichoke thistles blanketed the creek flats and slopes, horehounds had spread everywhere, boxthorn bushes crowded the slopes and plains, and other weed species filled the gaps. Erosion gullies scarred the steep slopes. Rubbish was piled here and there.

Achieving National Park Status

In order to rehabilitate the environment and get it back to the flourishing landscape it once was, the National Park Service (NPS) declared an area of 65 hectares (160 acres) as a National Park, on 12th March 1972. The NPS was propelled into action by the Friends of Organ Pipes (FOOPS), a group of conservation activists. The group was the first of its kind in Australia.

Over time — once in 1978 and then again in 1997 — amendments to incorporate more land were added to the Act. Works to remove the artificially introduced vermin and weeds and reintroduce natural vegetation and wildlife to the park continued throughout.

Archaeological Remnants at the Park

As a result of human settlement there are various archaeological elements in the park. There is a plum tree orchard, Jackson Bay Fig, and stables that were created and planted by the Hall family, who lived there between 1870 and the 1920s.

Be sure to keep an eye out for fossil pockmarks of sea snails, sea worms and extinct floating animals in the sandstone bedrock, which dates back 400 million years. These fossils and the prevalent sedimentary rock indicate that the park was once an ocean.

Our thoughts…

Organ Pipes National Park is important to the region as a “centre for education" on the environment's various geological, fauna and flora attributes. These various components invite visitors to be inquisitive in their exploration of the park and suss out the best picnic places, wildlife viewpoints, walking routes, and swimming spots!

Interested in finding more places like this? Why not try one of our Melbourne Scavenger Hunts — work as a team to overcome cryptic riddles and allow yourselves to be swept off the beaten track on a journey to discover all the quirky bars and unusual sites Melbourne has to offer.

Alternatively, please see further information about the Organ Pipes National Park below.