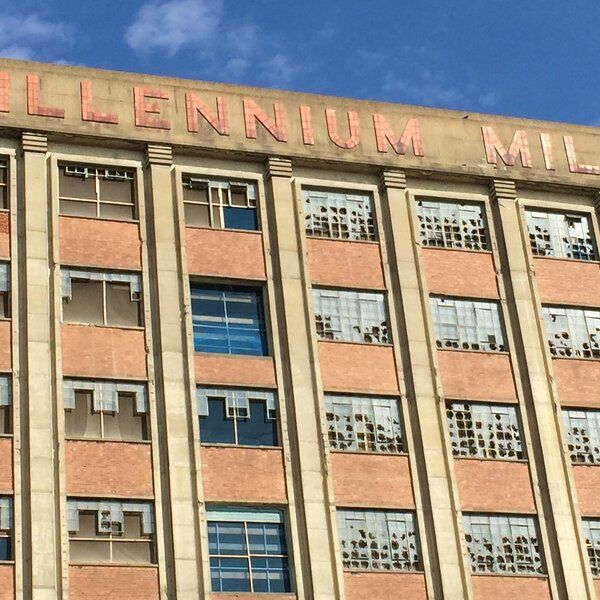

To modern eyes, the only striking detail of Holborn Viaduct appears to be its ornate, bright red colour and gold details. But make no mistake, there’s mastery at work here.

Londoners and visitors alike barely pay this lesser-known London landmark a second glance, and to be honest, why would you? Today, Holborn Viaduct is a thoroughfare that takes drivers, passengers and pedestrians from the City of London to Holborn, and perhaps its usefulness is what detracts from its fame.

But what is this giant red bridge doing here when it isn’t getting us from one place to another? Why was it needed in the first place? And what does it tell us about the London that once existed?

Let’s take a closer look at how Holborn Viaduct came to be, what its uses are, and what secrets it conceals about London’s past…

What is the Holborn Viaduct?

Before we go into what led to the Holborn Viaduct being built, we need to answer a very important question: what is the Holborn Viaduct?

Unless you’re an engineer, it’s not as silly a question as it sounds.

Simply put, Holborn Viaduct is a striking road bridge in the heart of the City of London, connecting Holborn on the west with Newgate Street and the financial district to the east.

Though it’s hard to imagine, it actually spans the valley of the now-covered River Fleet, which once created a natural divide between the two areas. By elevating traffic above the steep descent into Farringdon Street, the viaduct provides a much smoother and more direct route across one of London’s busiest thoroughfares.

The History of Holborn Viaduct

London Before Holborn Viaduct Was Built

Now we’ve got that out of the way, we can get into the good stuff. What was it like here before Holborn Viaduct was built? Well, pretty awful, actually.

Before Holborn Viaduct was built, Londoners had to cross two steep hills, Snow Hill and Holborn Hill, to get from one side of the Fleet to the other. Naturally, this made crossings tricky even in the best weather conditions, especially for London’s cabhorses.

As with many lost snippets of Victorian London’s past, we can ask Charles Dickens to lend a hand with setting the scene:

“Near to the spot on which Snow Hill and Holborn Hill meet, there opens, upon the right hand as you come out of the City, a narrow and dismal alley leading to Saffron Hill. In its filthy shops are exposed for sale huge bunches of second-hand silk handkerchiefs, of all sizes and patterns ; for here reside the traders who purchase them from pickpockets…” - Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist

Doesn’t sound like somewhere you’d want to hang about, does it? The City of London certainly didn’t think so, and not just because the traffic was bad.

In the mid 1800s, London wasn’t a pleasant place to live for many people. A spike in the population and redevelopment projects pushed poorer people out of the city and into slums, and as a result, the city’s roads and sewage systems were in desperate need of an overhaul.

Luckily, these ambitions could coincide on many if not most projects, and such was the case here. Some of the best minds of the age were brought in to create Holborn Viaduct, including William Haywood, and Rowland Mason Ordish.

The Engineers, Architects and Artists Who Created Holborn Viaduct

The main practical genius behind Holborn Viaduct was William Heywood, the City Surveyor, who designed the viaduct’s sweeping roadway and the iron arches that carried it across the valley of the River Fleet.

Alongside Haywood was Rowland Mason Ordish, the chief engineer. If you haven’t heard of him before, Ordish’s CV is an astonishing read. He was the engineer behind several global landmarks, including the dome of Royal Albert Hall, Albert Bridge, and further afield, Cavenagh Bridge in Singapore.

But from the offset, Holborn Viaduct was designed to be beautiful as well as brilliant. The City also enlisted some of the finest sculptors of the day to add sculptures and decorative details to make the final project stand out in a good way.

To this day, the parapets of the pavilions are crowned with statues that celebrate Victorian ideals. On the south side, Henry Bursill sculpted figures representing Commerce and Agriculture, while on the north side the firm Farmer & Brindley produced statues of Science and Fine Art. Adding a local civic touch, there are also effigies of two historic Lord Mayors of London, William Walworth and Henry Fitz-Ailwin.

Demolishing History To Make History

However dingy and rundown the area might have been, like many Victorian infrastructure projects, the creation of Holborn Viaduct in the 1860s came at a cost.

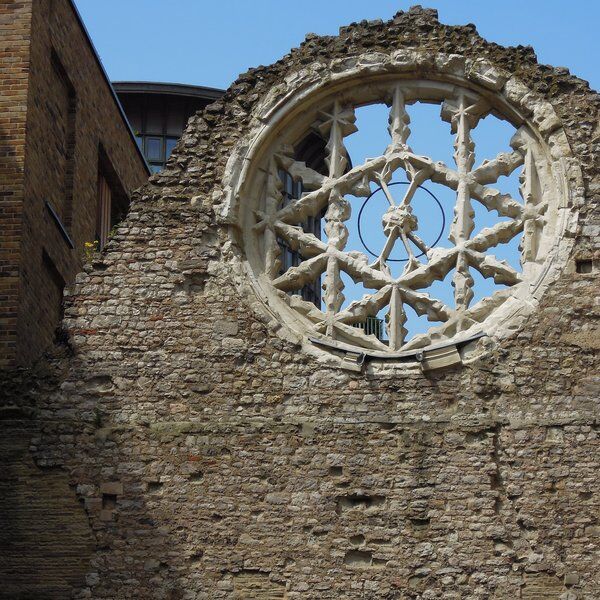

To carve a clear, elevated roadway across the valley of the River Fleet, a swathe of older streets and buildings had to be swept aside.

The works displaced part of the dense medieval street pattern that had grown up around Holborn Hill and Farringdon Street. Narrow lanes, small workshops, and taverns (many dating back centuries) were cleared to make way for the new viaduct and its approaches. Entire blocks were demolished to allow for the four corner pavilions and the broad carriageway above, permanently altering the character of the neighbourhood.

Most notably, the Church of St Andrew Holborn narrowly escaped destruction, standing just to the west of the viaduct’s line. Its churchyard wasn’t quite so fortunate: an estimated 11 to 12,000 remains were reinterred elsewhere.

For us, the most interesting building believed to have been destroyed to make way for Holborn Viaduct was the Saracen’s Head, a pub Charles Dickens mentions in Nicholas Nickleby. It once stood on Snow Hill, and it’s where the character Wackford Squeers stays overnight in the novel. Its loss was lamented in several newspapers (but only twenty or so years after the fact). It was probably a great place for eavesdropping, though.

Teething Problems: Holborn Viaduct and Victorian Vandals

Even with the grandeur and geniuses on board required for ambitious projects like these, no project truly gets off without a hitch and Holborn Viaduct wasn’t without exception.

The Viaduct opened on 6 November 1869, opened by Queen Victoria, no less, but barely a week later, it began to show some teething issues. Namely, cracks started appearing in the granite pillars causing widespread alarm. Fair enough, we’d say.

However the engineers, and the newspapers, both reported that they didn’t affect the stability of the supports. That reassurance clearly wasn’t enough for some, as the newspaper archives reveal an interesting flurry of accusations that “hundreds of persons have been picking them (the granite pillars) with their hands and knives, greatly to add to the disfigurement” — Sun (London) - Saturday 20 November 1869.

Visiting Holborn Viaduct Today

It almost goes without saying that Holborn Viaduct still carries busy traffic across the City of London, but it’s also a rewarding stop for anyone interested in history and architecture.

You’ll find it just a short walk from City Thameslink station, with Farringdon, Chancery Lane, and St. Paul’s tube stations are all within easy reach.

As you explore, take time to notice the four pavilions at each corner of the bridge, with their staircases leading down to Farringdon Street.

Look up at the statues of Commerce, Agriculture, Science, and Fine Art, as well as the figures of historic Lord Mayors William Walworth and Henry Fitz-Ailwin. And let’s not forget the ornate ironwork and lamp standards which also survive (and even survived The Blitz).

Find More Things to Do in London with CityDays

Since you’re here trying to find London hidden gems, what if I told you that we’ve done all the hard work for you?

At CityDays, we create hand-crafted treasure hunts, outdoor escape rooms, walking tours and exploration games all over London, including Central London, Mayfair, Shoreditch, Kensington and Southwark.

All you have to do is team up with your partner, friends, family or whoever to solve riddles, complete challenges and answer trivia to lead you on an unforgettable journey around London’s most intriguing streets.

The best part? We’ll recommend top-rated pubs, cafés and restaurants and give your team the chance to earn rewards by competing on our leaderboard.

CityDays gives you total freedom to start and finish whenever you like, take extra breaks if you want or need them, and it’s suitable for people of all ages.