Discover the Riverside Pimlico Gardens

Originally laid out by the renowned planner Thomas Cubitt, Pimlico is celebrated for its sophisticated garden squares and distinctive architecture. At the southern end of St George’s Square on Grosvenor Road, Pimlico Gardens is a public park that embodies the area's refined character. At its core, the gardens have well-tended lawns, benches, and a drinking fountain.

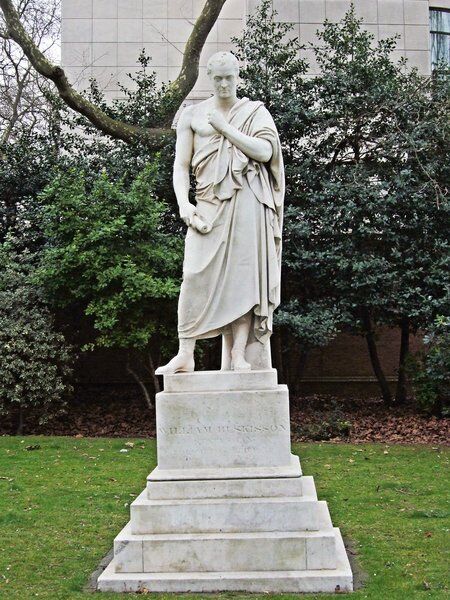

There is also a marble statue of William Huskisson, a celebrated statesman immortalised by the talented sculptor John Gibson. A quick 7- to 10-minute stroll from Pimlico Underground makes the park super accessible. And don’t be surprised if you catch sight of nearby boating bases and the gentle flow of the Thames; the park’s riverside charm is hard to miss!

Why Is It Called Pimlico Gardens?

Ever wonder how Pimlico got its catchy name? In its earliest days, the region was known by names like Ebury or “The Five Fields.” However, sometime in the late 17th or early 18th century, the moniker “Pimlico” emerged. There are several entertaining theories behind this change.

One popular tale suggests that it was named after a well-known publican—Ben Pimlico—famous for serving nut-brown ale at tea gardens near Hoxton. Others speculate that the name might have Spanish roots relating to drinks or even be linked to a Native American tribe. Whichever story tickles your fancy, the name Pimlico is now synonymous with the area.

The Early History of Pimlico Gardens

The land now known as Pimlico was once part of what locals referred to as “The Five Fields”—a vast area that also included what we now call Belgravia, Mayfair, and even parts of Knightsbridge. Back in the day, this patch of land was more famous for highway robbers than for its genteel charm!

The area’s transition began with twelve year old Mary Davies, who inherited the fields and married Sir Thomas Grosvenor (yes, at 12!). The Grosvenor family played a huge part in shaping the area’s destiny. Their involvement marked the transition of these unruly fields into the sophisticated neighbourhoods they are today.

Becoming Pimlico Garden Village

As London began to emerge from the devastating Great Plague and Great Fire, its people looked west for fresh opportunities. In 1825, Lord Grosvenor commissioned Thomas Cubitt to transform a marshy, unrefined tract into a coveted place for the upper echelons of society.

Using soil excavated from St Katharine’s Docks, Cubitt reclaimed the soggy terrain and laid out a neat grid of pristine white stucco terraces. His master plan centred on three grand garden squares that would eventually give rise to what we now celebrate as Pimlico Gardens.

Transformation and Social Change

By the late 1800s, while the district’s core maintained its upper and middle-class charm, certain pockets began showing signs of decline. The emergence of affordable Peabody housing estates transformed Pimlico into a melting pot of diverse communities—a marked shift from its formerly exclusive aristocratic character.

In the early 20th century, this tension between grandeur and grit became evident; even notable residents like Rev. Gerald Olivier remarked on the stark contrast by comparing the move to Pimlico with relocating to “West London slums.”

A New Chapter for Pimlico Gardens

The 1930s was the beginning of a new chapter for Pimlico. The construction of Dolphin Square—a complex of 1,250 upscale flats—quickly transformed the area into a hub for MPs, government workers, and other public servants, drawn by its proximity to Westminster. Meanwhile, Eccleston Square became the headquarters of both the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress, underscoring the district’s political significance.

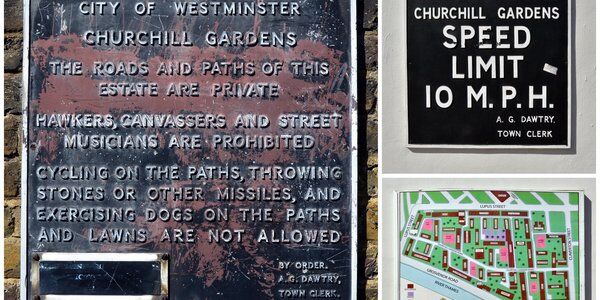

Although World War II and the Blitz left visible scars, Pimlico was revived with post-war regeneration efforts, including the development of new estates such as Churchill Gardens and Lillington & Longmoore Gardens. By the mid-20th century, Pimlico had firmly reestablished itself as a desirable and fashionable part of Central London, especially with the extension of the Victoria Line in 1972.

Pimlico’s Important Buildings

Pimlico also consists of several noteworthy buildings:

- Dolphin Square: Constructed between 1935 and 1937, this impressive block of private apartments was once heralded as the largest self-contained flat complex in Europe.

- Other Gardens: Both Churchill Gardens and Bessborough Gardens are located nearby.

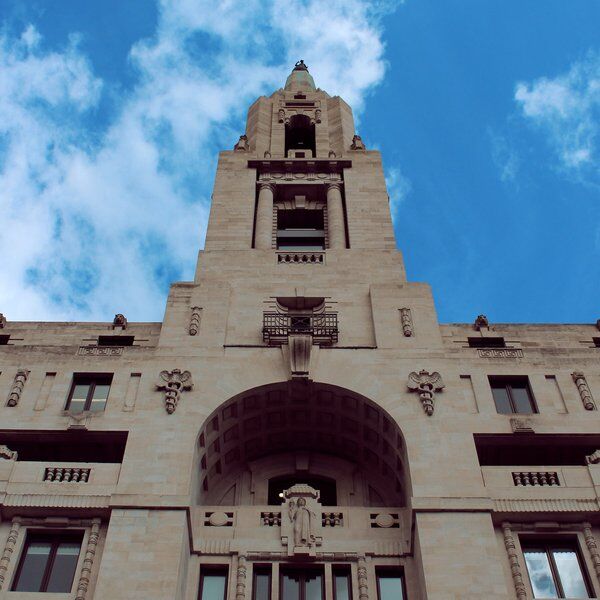

- Art Moderne Marvel on Buckingham Palace Road: Once the Empire Terminal for Imperial Airways, this sleek building—designed by Albert Lakeman in 1938—is a fine example of the Art Moderne style. Today, it houses the headquarters of the National Audit Office.

- Iconic Churches: Stroll through the area and you’ll encounter several churches, including St Gabriel’s in Warwick Square, St Saviour, and St James the Less.

- Tate Britain and Beyond: Although technically located in the Millbank ward, Tate Britain is just a short walk away. Meanwhile, the now-demolished Pimlico School was once a striking example of Brutalist architecture.

Pimlico’s Famous Faces

Over the years, the Pimlico area has been home to a veritable who’s who of influential figures:

- Sir Winston Churchill graced 33 Eccleston Square, leaving behind a blue plaque.

- Joseph Conrad, the Polish-born novelist known for his profound storytelling, once called 17 Gillingham Street home.

- Aubrey Beardsley, the celebrated illustrator, resided at 114 Cambridge Street.

- Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first president, and Charles de Gaulle, the iconic Free French leader, also found a place in Pimlico.

- And the list goes on— from the musical genius of Paul Weller to the cinematic charm of Bill Nighy and even the spooky legacy of Bram Stoker, author of Dracula.

Pimlico Gardens in Pop Culture

If you think Pimlico is all about garden squares and history, think again—it’s also a star in its own right in the world of pop culture!

On the Big Screen

Pimlico has served as the backdrop for a number of classic films:

- The 1940 version of Gaslight used the area’s moody charm to enhance its suspenseful narrative.

- The delightful 1949 Ealing comedy Passport to Pimlico put the neighborhood in the spotlight, showcasing its quirky appeal and timeless elegance.

Literary Inspirations

Writers and critics have long found inspiration in the character of Pimlico. In Orthodoxy, G.K. Chesterton famously mused about the area, suggesting that Pimlico’s greatness stems not from grandiosity but from being deeply loved. Meanwhile, Barbara Pym drew on the beauty of St Gabriel’s Church to inspire settings in her works.

Visiting the Pimlico Gardens

Ready to experience Pimlico Gardens for yourself? Here’s everything you need to know to plan your visit.

Getting There and Around

Pimlico is wonderfully connected to the rest of London:

- Tube and Rail: The area is served by Pimlico station on the Victoria line and is a stone’s throw from Victoria station, which also links up with the District and Circle lines. National Rail services to London Victoria are also available.

- Buses and Bikes: Bus routes 24, 360, and C10 make stops in the area, and you can hop on one of the many Santander Cycles docking stations scattered throughout.

- River Rides: For a change of pace, riverboat services from Millbank Millennium Pier offer scenic trips to Waterloo and Southwark.

- Opening Times and Accessibility: Designed to be accessible for everyone, the gardens have disabled access and are open from 8:00 am until dusk.

Explore Beyond the Pimlico Gardens with CityDays

If exploring London’s historical sites sounds like your kind of adventure, why stop at the Pimlico Gardens?

CityDays offers immersive scavenger and treasure hunt tours across London (and the world!) that bring history to life in a fun, interactive way.

Our urban adventure games blend riddles, challenges, and fascinating historical facts to take you on a journey through hidden gems and iconic landmarks.

So, ready to step into the past? Book a CityDays adventure and see London like never before.