Stroll along Pemberton Row and take a right onto Gough Square, and you’ll be met with the home of one of the English language’s greatest greats: Dr Johnson’s House.

At first glance, there isn’t much that sets this pre-Georgian, four-storied, brown brick building apart from its neighbours. There is the familiar “missing” window in the attic that makes all passersby who notice it elbow their friend in the ribs and say: “window tax!”. The four steps leading up to it are as familiar a sight in London as signs for the Tube.

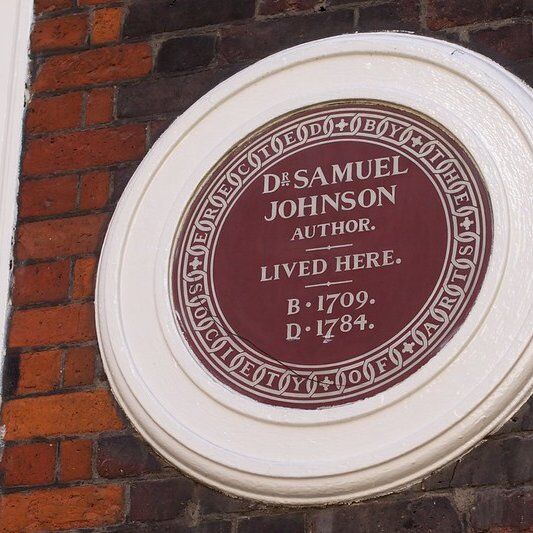

But there, sandwiched between two large white-framed windows on the left side of the building is not a blue plaque, but a red one. It reads: “Dr Samuel Johnson, author, lived here. B. 1709. D. 1787.”

To discover the true intrigue that lies beyond this deceptively ordinary façade, we must mount the steps and open the door to one of the most intriguing buildings in London, Dr Johnson’s House.

Come with me as we uncover its secrets, and if you read to the end, I’ll even introduce you to Hodge…

Dr Johnson’s House: A Home For Hire

To the untrained eye, Dr Johnson’s House could pass for Georgian architecture.

In actual fact, it was built at the end of the 17th century, during the reign of William III, commissioned by a wealthy wool merchant by the name of Richard Gough (hence the name of the square). Gough later became the director of the East India Company in 1713.

As they were built after the Great Fire of London that started on Pudding Lane in 1666, the houses around Gough Square were built using timber frames and bricks, in accordance with new fire safety regulations. Despite the use of sturdier building materials, Dr Johnson’s House is the only original home left in the square.

Dr Johnson did not purchase number 17 Gough Square, but spent just over 10 years there as a tenant (from 1748 until 1759). At this point in his career, Johnson was busily working on compiling the Dictionary of the English Language, a feat he undertook largely from inside the house’s garret.

After Johnson vacated the premises in 1759, 17 Gough Square became the home of new lodgers before being transformed for other uses, including a bed and breakfast and a printers’ workshop.

In 1911, the building was well and truly wilting: water readily leaked through the roof and it was in no condition to be considered hospitable. Its future looked rather bleak, until a Liberal MP by the name of Cecil Harmsworth stepped in to save it.

Dr Johnson’s House reopened to the public in 1914, and during World War II, the curator of Dr Johnson’s House and her daughter were allowed to run a small canteen there for the Auxiliary Fire Service. Later, the house became a social club for the firemen, offering them a place to rest during the Blitz and other air raids.

Because it was one of the tallest buildings in the area, Dr Johnson’s House was also used as a lookout point. The house was hit several times during the war, the Garret was badly damaged, and the roof had to be replaced. However, we must pay our thanks to the efforts of the firemen: the fires were always put out in time, and the house was saved.

Dr Johnson’s House: A Tenacious Tenant

We will delve more deeply into Dr Johnson’s House, and of course, his workings on the dictionary, but first we have a detour to take. Buckle up, because it takes us all the way to Staffordshire, where the young Samuel Johnson first opened his eyes.

Some stories write themselves, and that is certainly true of Johnson’s early life. He was born on 18 September 1709 above his father’s bookshop in Lichfield, Staffordshire. His parents, Michael and Sarah Johnson, were 53 and 40 years old respectively.

Johnson’s early life was marked by poor health and financial hardship, but through perseverance and a blessing from Queen Anne to “rid” the young Jonhson of scrofula, things began to improve. His education began from the age of 3, where his mother taught him to memorise and recite passages from the Book of Common Prayer.

Dr Samuel Johnson went on to become one of the most influential figures in English literature: a writer, critic, poet, lexicographer, and above all, a master of the English language. Today, he’s best remembered for creating A Dictionary of the English Language, the piece of work that makes Dr Johnson’s house worthy of visiting.

And if you’re wondering about his legacy, I like this passage from a 1937 edition of the Staffordshire Sentinel, writing 150 years after Johnson’s death:

“Johnson, the man, is likely never to be forgotten—emphatic, rough of tongue, profoundly learned, tender hearted, sensitive of conscience, brawny in his honesty and humanity, and contemptuous of humbug.”

What to See Inside Dr Johnson’s House

Wipe your feet folks, we’re heading inside the house and back in time for a while.

Well, actually, before we do, take a second look at the 18th-century front door, which still boasts its original anti-burglary fittings. These include a heavy chain with a corkscrew latch and a spiked iron bar above the fanlight, clever deterrents in a time before the Ring doorbell!

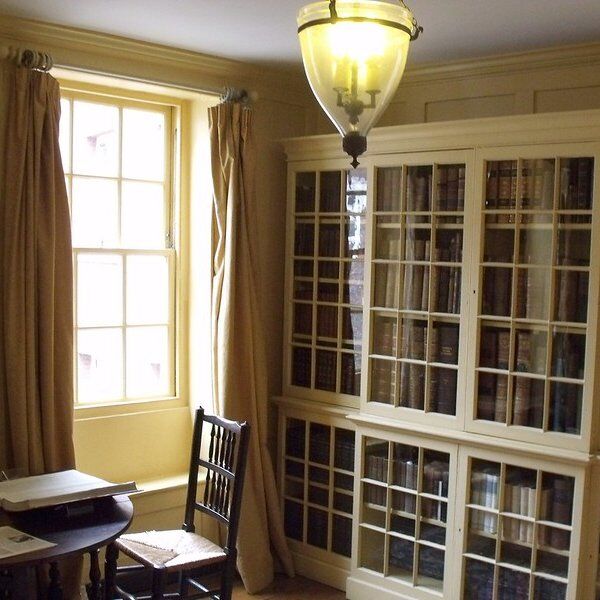

Now that we’re inside, the first thing you’ll notice is that Dr Johnson’s House has been incredibly well preserved. I’m lucky enough to be visiting on a beautifully sunny day, and sunlight is pouring in through the large windows making pools of light on the historic wood panelling and wooden floorboards.

Ahead of us is a graceful open staircase that winds through the house, and there’s also an unusual cellarette cupboard used for storing alcoholic drinks. If you really pay attention, you’ll even spot that even the door handles and coal holes are authentically Georgian.

The wonderful thing about visiting Dr Johnson’s House is that, unlike many historic houses, visitors are free to sit and stay a while. You can even perch on the chairs and window seats in each room, soaking in the quiet, bookish atmosphere that once surrounded Johnson as he compiled his famous dictionary.

Writing a “Masterpiece” at Dr Johnson’s House

Visiting in 2025, the first thing that strikes me is that Dr Johnson was WFH (working from home). While he was unlikely to have been disturbed by Zoom calls or Teams meetings, it is strangely comforting to imagine him sipping on a cuppa the way many of us do today.

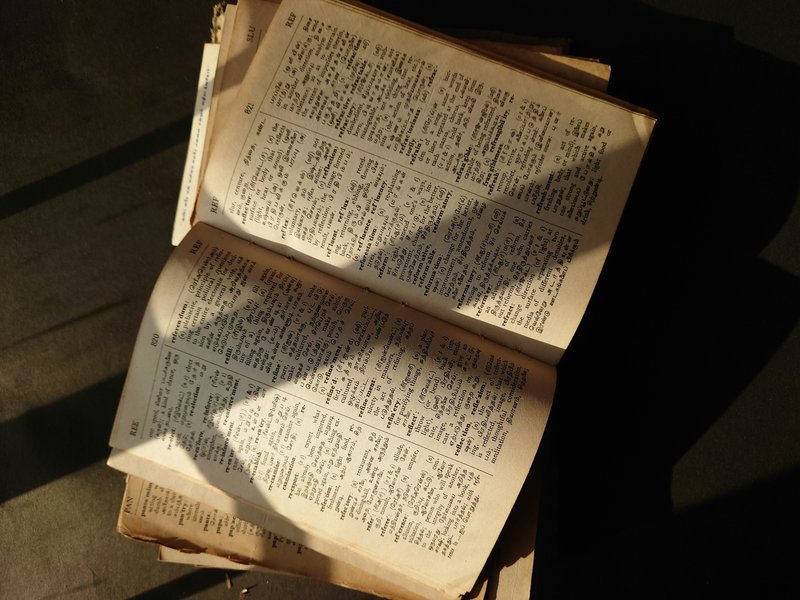

However, it’s important to understand that when Dr Johnson was working on A Dictionary of the English Language in 1755, he wasn’t just compiling a list of words. He was shaping the way English would be understood and taught for generations. But for all its scholarly weight, Johnson’s dictionary is also full of wit, charm, and a few surprising quirks…

It Took One Man (and a Few Helpers) Eight Years

Unlike modern dictionaries compiled by large teams, Johnson completed the dictionary with just a handful of assistants, all working in his house at 17 Gough Square. And like with many grand projects, what was expected to take three years took eight. Still, considering the scale, over 42,000 entries, it was a monumental achievement.

Some Definitions Were Hilariously Opinionated

Serious, fastidious and hardworking he may have been, but Dr Johnson had a sense of humour.

As anyone who has found themselves painfully early in a project that is taking much longer and proving to be harder than first imagined can attest, the entry he gave for “dull” is a thing of magic:

- Dull: Not exhilaterating (sic); not delightful; as, to make dictionaries is dull work.

And yes, it really amuses me that Dr Johnson spelt “exhilerating” like that!

It Wasn’t the First, But It Was The Best (At the Time)

Other English dictionaries existed before Johnson’s, but none were as comprehensive or consistent. His work set a new standard and remained the leading dictionary until the Oxford English Dictionary began to take over more than a century later.

Before Johnson’s work came along, many dictionaries were used more for translations (e.g. Latin to English) and didn’t contain most words used in common parlance.

It Wasn’t Commissioned by the Government

Unlike the French or Italian dictionaries backed by royal academies, Johnson’s was funded by a group of publishers. He worked independently, which may explain the personal flavour in many of his entries. And perhaps explains why he didn’t find it “exhilaterating” all the time!

Dr Johnson’s House: A Well-Remembered Man

In 1937, crowds gathered in St Paul’s Cathedral to commemorate 150 years since the death of Dr Samuel Johnson.

This was unusual for a few reasons: firstly, Samuel Johnson was buried in Westminster Abbey, not St Paul’s. Secondly, Johnson had long been out of living memory. Why commemorate his death?

The answers are quite straightforward. A memorial to Johnson had been placed in St Paul’s Cathedral, as well as in his hometown, Lichfield. Further, Johnson’s contribution to the English speaking world had changed society so enormously that 150 years after his death, people were still building on his earlier work.

Johnson laid the foundations for many of the things we take for granted today: spellcheck (we all love to hate it, don’t we?), the red squiggly line when we make typos, and the saviour of many essays: “synonyms”.

Up and down Britain, even in villages mere miles apart, there are disagreements about which comes first, “lunch” or “dinner”; what to call a woodlouse, and intriguingly, whether “tea” is a meal, a drink, or both.

But one thing is certain. A trip to Dr Johnson’s House brings you nearer the literary beginnings of something that changed the English-speaking world. Namely, a bit of order to our everchanging language.

Hodge’s House

I promised you if you got to the end of the article that I’d tell you about Hodge, and I’ve kept my promise. But I also have to introduce you to Lily, and to the other nameless felines that Johnson cared for throughout his life.

You see, no visit to Dr Johnson’s House would be complete without meeting Hodge, at least in statue form. Hodge was Dr Johnson’s beloved black cat and has become something of a legend in his own right. You’ll find his statue just outside the house, perched proudly atop a dictionary, with an oyster shell at his feet (one of Johnson’s favourite treats to give him).

Johnson was a famous cat lover, a personality quirk that was immortalised by his friend and biographer James Boswell. Unlike many people of his time, who saw animals as little more than property, Johnson treated Hodge with kindness and dignity. He even insisted on buying Hodge’s medicine himself, rather than sending a servant, so the cat wouldn’t be seen as a nuisance.

Today, the statue stands as a tribute not just to a pet, but to Johnson’s quiet compassion, and his belief that even a humble housecat deserved respect. And as for Lily?

Johnson described her to Susanna Thrale in a letter dated 18 November 1783: “Lily the white kitling, who is now at full growth and very well behaved’.

Explore London with CityDays

Interested in finding more fun things to do in London?

Discover London’s secret sights and noteworthy nooks by playing one of our London treasure and scavenger hunts, food experiences, escape room games or walking tours.

You’ll find curated trails and hunts all over London, including Central London, Mayfair, Shoreditch, Kensington and Southwark.

The best part? We’ll recommend top-rated pubs, cafés and restaurants and give your team the chance to earn rewards by competing on our leaderboard.

Take the stress out of planning your visit to London and book your adventure today!

Not visiting London this time? Don’t worry, you’ll find us all over the world.