What is Guilfoyle’s Volcano?

Despite its dramatic name, Guilfoyle’s Volcano is not a volcano in the typical sense of the word. But that doesn’t make it any less interesting.

Guilfoyle’s Volcano is actually a cleverly designed 150-year-old ornamental reservoir. The original ‘volcano’ was designed by Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens' most influential Director, William Guilfoyle, in 1873 as a backup water source solution. As it turned out, the gardens didn’t require Guilfoyle’s ingeniously designed reservoir, and it fell into disuse and later disrepair.

Guilfoyle’s volcano was later redesigned by the landscape gardener Andrew Laidlaw in 2010, where it remains to this day.

History of Guilfoyle’s Volcano

The story of Guilfoyle’s Volcano is just one of many that make the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne a must-visit for tourists to Victoria’s capital.

It’s far too easy to dismiss it as a hill, a disused body of water or an unconventional swirling path lined with succulents. Don’t be fooled. How it came to be there is a tale of Victorian engineering, a pioneering underdog botanist and a resurgence of interest in preserving access to green spaces.

Read on to find out more.

Who was William Guilfoyle?

William Guilfoyle was born in Chelsea, London in 1840. His father, Michael Guilfoyle, was a relatively well-known gardener in the UK, where he worked for the esteemed Royal Exotic Nursery. His mother, Charlotte Guilfoyle, née Delafosse, was of Huguenot ancestry. The couple had four children including William, and in 1849, the family set sail for Sydney, Australia to expand Michael Guilfoyle’s reputation as an expert nurseryman.

Botany and a love of plants was in young William’s blood. While attending Lyndhurst College in Glebe, William watched his father’s nursery empire grow ever larger. His father’s business, Guilfoyle’s Exotic Nursery, in Double Bay became world-renowned for its excellent garden, boasting exquisite species of flowers and trees from South America, Australasia, and Asia. Its acclaim was so great that a visit to the Guilfoyle’s Exotic Nursery was on the-then Duke of Edinburgh’s (Prince Alfred, Queen Victoria’s second son) Sydney itinerary in 1869. The street Guilfoyle Avenue in Double Bay is named after Michael Guilfoyle and his nursery.

His father’s botanical knowledge and extensive network of scientists primed young William for plant-based success. In 1868, William went aboard the HMS Challenger as a member of the scientific staff. The voyage cruised around the Pacific, and William’s experience would later become vital inspiration for his future role as Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne - and in particular, in designing Guilfoyle’s Volcano.

William Guilfoyle and The Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne

The Melbourne Royal Botanic Gardens was established in 1845, though in its initial state it would be barely recognisable to today’s visitors. Little more than swampy marshland, the five acre plot was popular with frogs and birdlife - but not with Melbournians. Before Guilfoyle could create his eponymously named Guilfoyle’s Volcano, he had some bigger plans to sort out…

William Guilfoyle Revolutionises Melbourne Royal Botanic Gardens

On 21st July 1873, William Guilfoyle replaced the esteemed German-Australian botanist, Baron Ferdinand von Mueller, as Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens. Mueller was furious and pessimistic. His sentiment was echoed by some of the board members: they felt Guilfoyle was too young and too naive for what was a huge responsibility.

After meeting the-then 33-year-old William Guilfoyle, however, the board was unanimous: they had found the man for the job. Guilfoyle’s personality could be summarised in four words: swift, unhesitating, proactive and ambitious. Within days of accepting the position, Guilfoyle could be seen strolling around and inspecting the gardens, taking in the sheer amount of work to be done in his stride.

According to the September 1966 edition of Walkabout, one of Guilfoyle’s first acts as Director was to clean and clear the gardens’ lake which had become clogged with weeds that had killed the lake’s fish population. To remedy the situation, Guilfoyle fabricated a DIY weed cutter and attached it to the bow of his rowing boat and attached large floating rakes behind the vessel. He spent hours rowing up and down the lake, chopping and raking up the weeds himself until it was clear. Like a painter signing off a masterpiece, he planted water lilies and established a new fish population in the lake.

But not all of the Royal Botanic Gardens could be rescued with Guilfoyle’s combination of ingenuity and hard work. His plans were ambitious and involved more starting from scratch than remodelling Mueller’s gardens - much to the chagrin of the Board’s treasurers. Not to be deterred, Guilfoyle’s instructions were clear: it was his way or the highway. When he was met with opposition, he ploughed ahead with his plans anyway.

This stubborn streak could have landed Guilfoyle in trouble, but his ideas and especially their results spoke for themselves. Guilfoyle removed Mueller’s stiff, straight paths and replaced them with winding ones. He moved trees even when warned that they would probably die - his knowledge of trees, handed down from his father, reassured him that most of them would not. He planted sweet-smelling and vibrant flowers for all to enjoy, appreciating that most modern people’s enjoyment of plants was limited to their beauty, rather than their usefulness.

Additionally, Guilfoyle could see that the Royal Botanic Gardens were as useful for recreation as they were for science. He designed a Rose Pavilion to be used in the hot months, offering much needed shade from the Australian sun (or cover from Melbourne’s fierce downpours).

But Guilfoyle was also a scientist. Like Mueller before him, he appreciated plants for their useful properties and believed in their importance. He reached a compromise between beauty and knowledge when, in the 1880s, he opened a medicinal garden and later, in 1892, the Museum of Economic Botany and Plant Products opened its doors.

By the time William Guilfoyle’s Eden was complete, its reputation had spread around the world.

When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes series, visited Melbourne Botanical Gardens in 1920, he said:

“[it] is, I think, absolutely the most beautiful place that I have ever seen. I do not know what genius laid them out, but the effect is a succession of the most lovely vistas, where flowers, shrubs, large trees and stretches of water, are combined in an extraordinary harmony.”

Guilfoyle’s Volcano: A Dormant Genius Idea

But one of Guilfoyle’s many ingenious ideas did not, initially at least, feature in the glowing praise of his work: Guilfoyle’s Volcano.

As even non-expert gardeners know, plants need two things to survive and thrive: sunlight and water. In a five acre garden, a reliable water source is a vital component in ensuring the plants’ longevity. Guilfoyle, the perfect combination of artist and scientist, used his sketchbook to document concepts for how to “combine the useful with the ornamental” and the result was a bluestone reservoir modelled after a Vanuatu volcano.

Guilfoyle built his reservoir in the highest point of the south-eastern corner of Melbourne Botanic Garden in 1876, just three years into his tenure as the Garden’s director. Its shape was inspired by Guilfoyle’s trip aboard the HMS Challenger in his early 20s, where he had been struck by the beauty of Vanuatu’s volcanic landscape.

The idea occurred to Guilfoyle that instead of lava pouring out of his volcano, water aided by gravity could be delivered safely and efficiently to his beloved plants without sacrificing the beauty of the landscape.

The idea was brilliant, but it turned out to be wholly unnecessary. The reservoir took too long to refill, and besides, the Garden’s main water supply came from the Yarra River, and was later updated to be connected to Melbourne’s water mains, each more than capable of supplying sufficient quantities of water. Guilfoyle’s Volcano fell into disuse, and by the 1980s, it was emptied and public access was denied.

Guilfoyle’s Volcano is Reborn

After just a decade, plans were drawn up in the 1990s which would revive Guilfoyle’s Volcano. It was, after all, a historic part of the gardens, and in a world that was gradually shifting towards increased climate awareness, demand for a self-sufficient watering system was on the rise.

In 2008, plans for redeveloping Guilfoyle’s Volcano were approved. Local landscape architect, Andrew Laidlaw, was put in charge of re-designing the space. The only material from Guilfoyle’s original plans that Laidlaw had to go upon was a single small watercolour artwork - not nearly enough to recreate his vision.

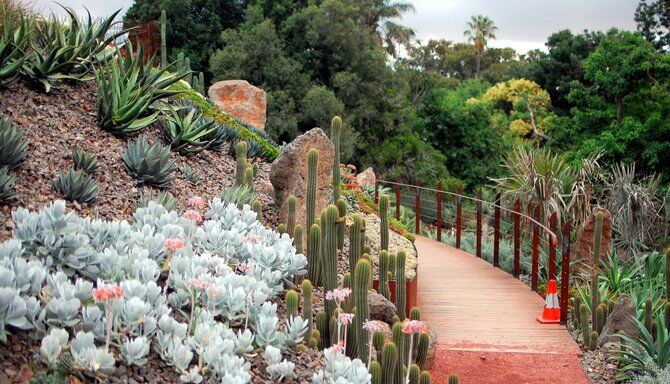

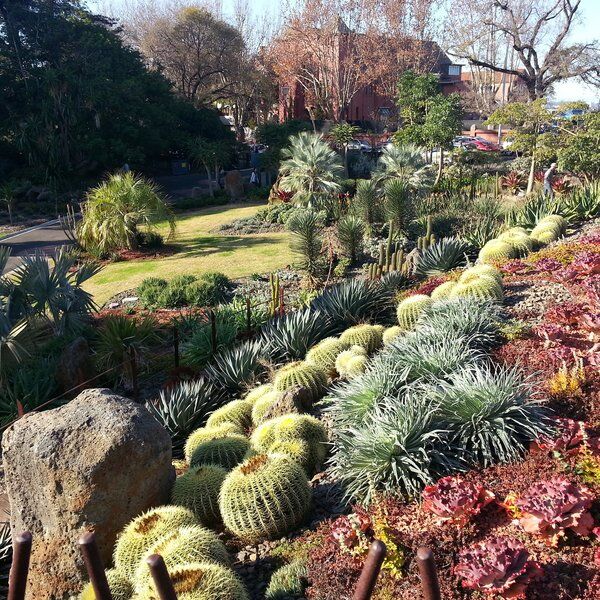

But Laidlaw, like Guilfoyle, wasn’t put off by challenges. He set about planting a range of flora that would evoke the volcanic element of the design. Low succulents which turn red without water contrast with the tall Torch Cacti from Argentina, while plump bulbous Golden Barrel cacti from Mexico perch among the many rocks and native Australian plants in varying shades of red, orange and green.

The reservoir itself was also updated to act as a stormwater capture, filtration and reticulation system: or, simply put, to recycle, filter and resupply stormwater to the Gardens.

According to the Royal Botanic Gardens, around 60 megalitres of stormwater are captured and redistributed to wetlands and lakes in the Gardens every year.

Visiting Guilfoyle’s Volcano Today

Ironically, William Guilfoyle’s greatest legacy lives on mostly through his eponymously named Volcano, despite the fact that in its current state, it is a modern interpretation of Guilfoyle’s vision for the Gardens.

Today, people still flock from all over the world to admire Melbourne’s spectacular Royal Botanic Gardens - and, of course, to admire Guilfoyle’s Volcano.

For casual visitors, a walk along the spiral walkway leading to the top of the ‘volcano’ is well-worth the effort. At the end lies panoramic views of the gardens (and the satisfaction of the climb!).

Guilfoyle’s Volcano is also a great introduction to learning more about plant diversity and adaptability: the plants featured in the design have evolved from ever-increasingly limited water supply, teaching visitors about the importance of sustainable horticultural practices.

Visitors wishing to explore Guilfoyle’s Volcano can enter through Tecoma Gate for the most direct access.

Discover More about Melbourne with CityDays

Ready to discover more of what Melbourne has to offer?

CityDays have FOUR treasure and scavenger hunts in Melbourne to choose from, all of which combine the fun of an escape room with the historic facts and whimsical trivia of a walking tour!

For botanically-minded explorers, we recommend signing up to Botanical Bedlam for news about its upcoming release (you won’t want to miss it!).

Take the stress out of planning your visit to Melbourne and book your adventure today!

Not visiting Melbourne this time? Don’t worry, you’ll find us all over the world.