Discover Postman’s Park in London

Tucked away between the glassy office towers and old-world churches of central London lies a peaceful patch of green that’s full of surprising stories. Welcome to Postman’s Park—a place where pigeons waddle, squirrels scamper, and unsung heroes are remembered in beautifully tiled glory.

Just a short stroll north of St Paul’s Cathedral, this leafy little haven is steeped in Victorian history, memorials, and more than a few bones (literally—we’ll get to that). It’s flanked by Little Britain, Aldersgate Street, King Edward Street, and St. Martin’s Le Grand. It’s also a stone’s throw from the former site of the General Post Office (GPO), which, as you might guess, is where this park gets its name.

When the park opened to the public in 1880, it quickly became a favourite hangout for these GPO workers. Picture postmen on their tea breaks, letter sorters eating sandwiches in the shade, and office staff catching five minutes of peace before diving back into their duties. And just like that, the park earned its nickname—one that’s stuck ever since, even if postmen are now a rarer sight.

The Origins of Postman’s Park

Once upon a Victorian time, this Postman’s Park wasn’t a park at all—it was a trio of church burial grounds belonging to the following parishes:

- St Botolph’s Aldersgate (the church you can still spot beside the park)

- Christ Church Greyfriars

- St Leonard, Foster Lane

Over time, each of these burial grounds became heavily overused. The result? Graves were layered on top of each other, and eventually, the ground level rose significantly above street height—in fact, by the mid-1800s, parts of the park were up to six feet higher than surrounding areas and today the park is still slightly elevated.

As London’s population boomed and burial space dwindled, public health concerns began to rise. The infamous cholera outbreaks of the 1830s and 1840s pushed the city to rethink its burial practices. Open graveyards in residential areas? Not ideal.

So, between 1858 and 1860, St Botolph’s churchyard was decommissioned and transformed into a public garden. Human remains were removed or reinterred, gravestones were stacked neatly against the northern wall, and the area was re-landscaped for public use.

A Bit About the Churches Beneath Your Feet

Although St Botolph’s Aldersgate is the most visible of the trio today, its story is intertwined with those of its neighbouring parishes.

- St Leonard, Foster Lane was first mentioned in the 13th century but didn’t survive the Great Fire of 1666. Its ruins lingered for nearly 150 years before being cleared in the 1800s.

- Christ Church Greyfriars rose from the ashes of the Great Fire thanks to Sir Christopher Wren and absorbed the parish of St Leonard after its destruction. Its burial ground sat just to the east of today’s Postman’s Park.

Despite these parishes being gradually absorbed into the park—although not without a long and tedious ownership squabble between the church, the Post Office, the Treasury, and the City Parochial Foundation—they maintained their own burial grounds until they were closed.

Enter the Vision of George Frederic Watts

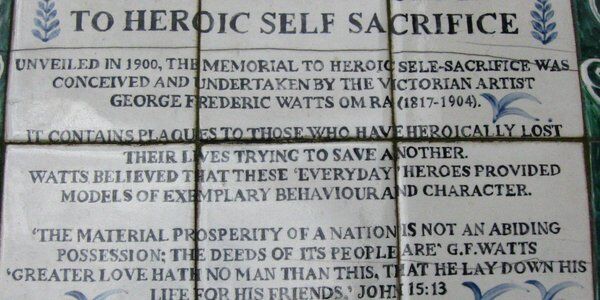

Now, let’s rewind to the tail end of the 19th century. Queen Victoria was celebrating her Golden Jubilee, and while most people marked the event with street parties and pudding, the famous Victorian painter George Frederic Watts had… a different idea.

Watts—ever the soulful and slightly macabre artist—suggested that the best way to celebrate the monarch’s long reign would be with a tribute to heroic deaths. Not stately portraits or royal pageantry, but real-life stories of everyday folks who had laid down their lives to save others. He hoped their tales of bravery would encourage the general public to live more nobly.

He first pitched a massive bronze statue called “The Monument to Unknown Worth.” But funding wasn’t exactly rolling in. According to Watts, if he’d asked to build a horse racing track in Hyde Park, the money would've materialized with no issues. Instead, his proposal to honour selflessness was met with polite silence.

Postman's Park and the Wall of Heroes

So how did we get from Watts, scribbling lofty ideas about national soul and “Unknown Worth,” to actual ceramic plaques tucked away in a peaceful London park?

Let’s just say… It wasn't a smooth ride.

After his grand proposal for a towering bronze monument landed with a collective Victorian shrug, Watts did what all determined dreamers do: he scaled down—but didn’t give up. If the nation didn’t want a colossal statue looming over Hyde Park, maybe it would accept something a little more… low-key.

Enter Postman’s Park.

It made perfect sense, really—what better place to honour everyday heroism than a park frequented by everyday people, especially postal workers who quite literally carried the weight of the nation’s communication on their backs?

Instead of bronze and marble, Watts turned to ceramic, partnering with his friend and tile wizard William De Morgan. De Morgan whipped up a series of beautiful yet budget-friendly plaques in calming hues of blue, green, and cream. They were affordable, weather-resistant, and had that charming Arts and Crafts look that still turns heads today.

By 30th July 1900, a modest wooden cloister was constructed in the park, and the first plaques were unveiled. It wasn’t the grand, sweeping monument Watts had envisioned—but it was something. Something meaningful. Something lasting.

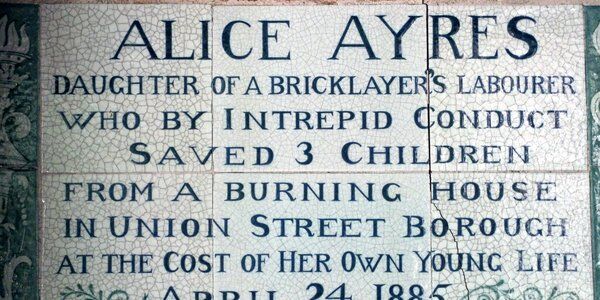

You’ll read about folks like:

- George Funnell, who perished trying to drag a barmaid from a burning pub.

- Mary Rogers, who handed her lifebelt to a child as their ship went down.

- Mrs. Yarman, who died carrying her elderly mother through smoke and fire.

- And Sarah Smith, a pantomime performer who died in a tragically flammable dress incident (and yes, hopefully she did get a refund).

And over a hundred years later? We’re still reading their names. Still moved. Still inspired.

The Tablets: A Quick Look at the Tiles

Aesthetically, the tiles are a bit of a patchwork—but a beautiful one. The earliest tablets, installed in 1900, were large, bespoke De Morgan creations. Then costs crept in and standard-size tiles took over. In 1908, a full batch of 24 was cranked out by Royal Doulton (because by then, De Morgan had moved on to writing novels). Later additions followed the Doulton style, with just a few in the original De Morgan design.

Today, the memorial contains a mix of materials, fonts and hues, but that adds to its charm. It’s like a quilt of kindness, stitched across time.

A Post-Watts Postman’s Park

Unfortunately, Watts didn’t live long enough to see the wall fully realized, but thankfully, Mary Watts, his equally passionate (and just as stubborn) wife, picked up the torch. Over the next few decades, she added more tiles—39 in total—until her own death in 1938. Then? Silence.

Without Mary, the tiles came to a halt. Only 52 out of the intended 120 stories of bravery made it onto the wall. And while there were murmurs of finishing the project over the years, the Watts Gallery was... let’s say, politely resistant. Their stance? The memorial’s incompleteness was a kind of poetry—a frozen-in-time tribute to Victorian values.

Blitz, Bureaus, and Benches: The Park’s Bumpy Years

As if losing its champion wasn’t enough, the surrounding neighbourhood had a rough mid-century. In 1940, the nave of nearby Christ Church Greyfriars was bombed during the Blitz. By then, the City of London’s population had shrunk and church pews were getting a bit dusty. Eventually, the remnants of Greyfriars became a memorial garden (with office space squeezed into the tower because: London real estate).

Meanwhile, St Botolph's Aldersgate—still watching over the park—dodged the wrecking ball and remained open. These days, thanks to its location in the financial district, its congregation is mostly weekday worshippers, so services are now held on Tuesdays. A bit quirky, but practical.

Postman’s Park Gets Sculptural: Policemen and Minotaurs

Postman’s Park hasn’t only been about humble heroes—it’s had its own brief flirtation with bold bronzes. In 1952, a statue of Sir Robert Peel, evicted from Cheapside for being a traffic hazard, found a short-lived home in the park. But when the police decided he’d be more at home at their training centre in Hendon, he was swapped out for a giant bronze Minotaur.

The mythical beast stood guard in the park until 1997 when it was rehomed to a nearby raised walkway. Apparently, the Minotaur needed a bit more legroom.

Listed Status

In the 1970s, someone finally said, “Wait, this place is actually pretty important!” And so, in 1972, the park’s charming Gothic drinking fountain and its western entrance were granted Grade II listed status, meaning they couldn’t be knocked down or dressed up without permission.

The Memorial itself also received protection in 2018. But this was a Grade II* listing. That little asterisk? It means it’s officially “particularly important.” Fancy that.

Art Imitates Neglect: Susan Hiller’s “Monument”

By the 1980s, Postman’s Park had become a bit of a hidden gem—more ‘out-of-sight lunch spot’ than sacred shrine. That’s where artist Susan Hiller stepped in. After noticing how the heroic plaques were routinely ignored by sandwich-munchers on park benches, she created Monument, a multimedia installation based on the memorial.

Viewers would sit facing away from the plaques while listening to Hiller’s musings on death and memory. It was clever, ironic, and a gentle scolding for our collective forgetfulness. The piece is now part of the Tate’s collection and is considered a cornerstone of British conceptual art.

Similarly, in 2013, a mobile app called ‘The Everyday Heroes of Postman’s Park’ was launched. You could point your phone at a tile, and it would tell you the story behind it—like a digital museum in your pocket. Sadly, the app is no longer available (RIP), but it was a fitting modern twist on an old-school idea.

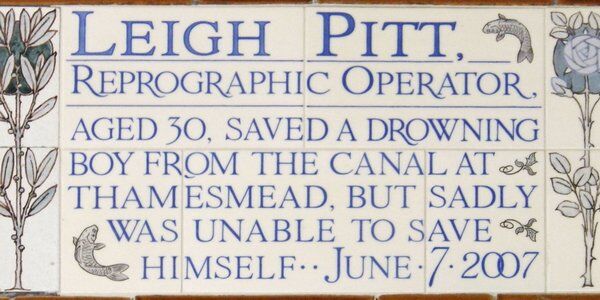

A New Hero in Postman’s Park: Leigh Pitt

After nearly eight decades of tile silence, the wall welcomed a new name in 2009: Leigh Pitt. Leigh was a print technician from Surrey who tragically died saving a young boy from drowning in a Thamesmead canal in 2007. A colleague, Jane Michele (now Jane Shaka), suggested his name be added, and to everyone’s surprise, the Diocese of London agreed.

Despite long-standing resistance from the Watts Gallery, Pitt's tile was installed—bringing the total up to 54. It marked a turning point: the possibility that the memorial might one day be finished after all.

The Friends of the Watts Memorial

In 2015, a group of dedicated enthusiasts formed The Friends of the Watts Memorial, a not-for-profit squad with one simple mission: protect, preserve, and (hopefully) complete the memorial. Working hand-in-hand with the City of London, the Bishop of London’s Office, and the Watts Gallery, the group hosts events, supports research, and spreads the word about this corner of heroism hiding in the city’s heart.

They’re also raising funds to conserve the existing tiles and perhaps even commission a few more. George and Mary would be proud.

The Garden Side of Postman’s Park

Postman’s Park isn’t just about the stories of bravery—it’s also a botanical treat. Step through the main entrance on King Edward Street, and you’ll find yourself embraced by towering shrubs and trees, including camellias that burst with colour in every shade imaginable.

Keep an eye out for the handkerchief tree, whose delicate floral branches put on quite the springtime show, according to the flower gurus at Kew Gardens. There are also lace hydrangeas and a whole bunch of seasonal blooms that get refreshed all year round. If you love a bit of nature with your history, this garden vibe adds a lovely layer to your visit.

Postman’s Park in Popular Culture

You might think this little green spot tucked away in London’s City is just a quiet corner, but nope—Postman’s Park has sneaked its way into some pretty cool pop culture moments. Ever seen the film Closer (2004)? That’s where the characters Dan (Jude Law) and Alice (Natalie Portman) first cross paths—right here in Postman’s Park.

Fun fact: Alice’s alias in the story is borrowed straight from the heroic names on the park’s famous memorial. Pretty neat, huh?

More recently, the park played a cameo role in the romantic flick The Last Letter from Your Lover (2021), acting as the backdrop for a key meeting between the leads. And if you’re a bit of a music buff, Phil Mogg from the band UFO even gave the park a shout-out in his 2024 album Moggs Motel—so it’s definitely earned its spot on the cultural map.

Visiting Postman’s Park

If you’re wandering around the buzzing streets near St Paul’s Cathedral, don’t let Postman’s Park slip under your radar. This hidden gem is a peaceful little oasis perfect for a breather, a bit of reflection, or even a quick lunch break.

The nearest tube stop is St Paul’s—just a quick walk away—and the park opens at 8:00 am and closes at dusk or 7:00 pm, whichever comes first. Just a heads up: it’s closed on Christmas Day, Boxing Day, and New Year’s Day. So plan your visit accordingly!

Bonus points: it’s totally free to visit!

Explore the Neighborhood Near Postman’s Park

If you’ve got time for a little more wandering, you’re in luck! Postman’s Park sits in a treasure trove of cool spots:

- The Blue Police Call Box: Just outside the park gates, you’ll spot an old-school London police box, perfect for a quick photo op.

- St Paul’s Cathedral: Only a 10-minute stroll away—a must-see for any visitor.

- Museum of London: Just 4 minutes on foot for some fascinating city history.

- The Old Bailey: A 7-minute walk if you want to peek at London’s historic law courts.

- Poets’ Corner: On the original site of St Mary Aldermanbury, only a 2-minute walk.

- Plus, charming gardens and remnants of the old London city wall nearby!

Explore Beyond Postman’s Park in London

If you’ve fallen in love with the quirky charm and hidden stories of Postman’s Park, why not keep the adventure going?

CityDays run awesome scavenger and treasure hunt tours all over London — and even worldwide — perfect for teams, friends, or anyone up for some serious fun and friendly competition.

These tours are a fantastic way to explore the city’s secret corners, solve puzzles, and bond over shared adventures. Whether it’s for team-building exercises or just a day out with friends, our hunts turn sightseeing into a game you won’t forget.

Ready to explore? Let’s make your next trip to London (and beyond) a memorable one, full of mystery, history, and a whole lot of laughs.